17 Aug On This Day in UB History: August 17 (Jeremiah Kenoyer)

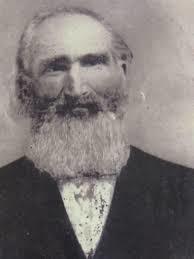

Rev. Jeremiah Kenoyer

Rev. Jeremiah Kenoyer was a true pioneer preacher. He began his ministry in frontier settlements in Illinois and Wisconsin. In the years ahead, he would help extend the United Brethren church into three new states–Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

At age 33, he heard that the new Home, Frontier, and Foreign Mission Board was recruiting ministers to go to Oregon. He offered to go if the board would pay $150 of his expenses. They agreed. With that amount, Jeremiah and Elizabeth Kenoyer committed themselves–and their seven children, ages 12 to a few weeks–to the 2000-mile journey.

The Kenoyers were penniless when they reached the Willamette Valley in Oregon. A grandson wrote that they left one or two milk cows with a ferryman because they couldn’t pay him. The Kenoyers immediately went to cousin Rev. Jesse Harritt, who lived near Salem. Kenoyer split rails and chopped wood to earn a living, and preached every night of the week and twice on Sundays.

Rev. T. J. Connor, who led the wagon train, once wrote, “I will put Jeremiah Kenoyer against any man I ever saw for the ability to call seekers to the altar or bring members into the church.”

Oregon Mission Conference was organized in 1855 and by 1861 had forty-eight preaching places and five hundred sixty-five members.

In 1868 (some sources say 1863), Kenoyer and his family–now 11 children, soon to be 13–moved to Washington Territory, where he continued as a pioneer itinerant until old age. He led efforts to establish what became Walla Walla Conference, and played a key role in sending workers from there to Idaho Territory in the 1870s.

The ministry ran deep in Kenoyer’s blood. His father was Rev. Frederick Kenoyer, and his mother was the daughter of Rev. J. G. Pfrimmer, who was instrumental in the UB church’s earliest days. Three sons, a son-in-law, and five grandsons of Jeremiah Kenoyer became ministers. One grandson, Fermin L. Hoskins, served as bishop 1905-1933.

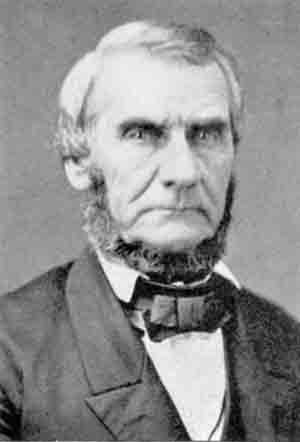

Bishop Milton Wright, who spent two years in Oregon, recalled hearing Kenoyer preach a sermon in which he “ground into the very dust the pro-slavery prejudices which spurned a quarterblood negro from the school by simple protest; and yet it was so masterful as well as kindly done, that no one could be seriously offended.”

Rev. Jeremiah Kenoyer died on August 17, 1906, in the state of Washington.

In earlier times, most of the longest-tenured United Brethren missionaries served in Sierra Leone. Today, the top three can be found in Asia. Two of them minister in restricted access countries, which means we can’t talk about them on the internet. The third is Jennifer Blandin.

In earlier times, most of the longest-tenured United Brethren missionaries served in Sierra Leone. Today, the top three can be found in Asia. Two of them minister in restricted access countries, which means we can’t talk about them on the internet. The third is Jennifer Blandin.

On August 7, 1964, Pauline O’Sullivan began a three-year term serving as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She was probably the first missionary to come from one of our mission fields–in her case, Jamaica. Her uncle, Rev. James O’Sullivan, a Jamaican, founded the UB mission work in Jamaica.

On August 7, 1964, Pauline O’Sullivan began a three-year term serving as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She was probably the first missionary to come from one of our mission fields–in her case, Jamaica. Her uncle, Rev. James O’Sullivan, a Jamaican, founded the UB mission work in Jamaica.