06 Sep On This Day in UB History: September 6 (Joseph Gomer)

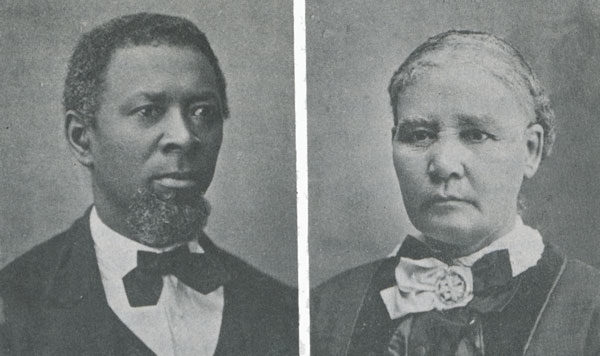

Joseph and Mary Gomer

Joseph Gomer passed away on September 6, 1892. At that point, he and his wife, Mary, had served under the United Brethren mission board in Sierra Leone for 22 years, superintending our work there the entire time. They were very, very good years. “Within United Brethren mission history,” wrote David Datema in 2016 for a college paper, “the Gomers stand out as elite missionaries.”

We established mission work in Sierra Leone in 1857, but our early efforts were frustrating and virtually fruitless. When the Gomers arrived in January 1871, we had been without missionaries for two years and had almost pulled out altogether. But almost immediately after the Gomers arrived, the work took off. Later that first year came the conversion of the powerful local chief, Thomas Stephen Caulker, who had been a thorn in the side to missionaries. Caulker and others told the Gomers, “We now see that Christianity isn’t just a white man’s religion.”

You see, the Gomers were black–the first black United Brethren missionaries.

Joseph Gomer grew up on a farm near Battle Creek, Mich., and despite the prejudice of white classmates, managed to get some schooling. He served as a cook during the Civil War. After being honorably discharged in 1865, he boarded a riverboat headed for Dayton, Ohio. On board he met a widow named Mary Green, who was also a gifted singer. After reaching Dayton, they were married. Joseph found work as a carpet layer, and later worked as a foreman in a mercantile house. He and Mary became leaders in Third United Brethren Church, a predominantly black congregation in Dayton which Miami Conference had started in 1858 as a mission project.

The Gomers applied for missionary service, but were initially rejected. Historian and former bishop William Hanby implied that their race had something to do with it, but it may have been more a case of Gomer not being a minister and lacking in education. Whatever the case, the Mission board was urged to reconsider the Gomers.

Joseph Gomer was perfect. He was a diplomat, a teacher, a peacemaker among the warring tribes. He became highly respected, and umpired many disputes among the Africans. He taught farming methods, which were applied on the mission’s 40-acre farm (produce, over 5000 coffee and cocoa trees, plus some animals). In 1875, he organized the first United Brethren church in Sierra Leone.

History writers note their abilities, their dedication to the work, and their spiritual fervor. But they also cite the Gomers’ skin color as a crucial difference-maker.

According to David Datema, the Gomers went to Africa during a window of time in the 1800s during which white Christians were open to sending blacks as missionaries–but a window which didn’t stay open long. Datema wrote, “For black Americans serving under white mission boards, signs of racism were prevalent and included lower pay, longer terms, shorter and less frequent furloughs, less promotion, and less educational benefits offered to their children.” Eventually, American mission boards reverted to preferring white missionaries.

Datema noted that the longest term served during that period by a white UB missionary was 3.5 years, compared to terms of six, six, and ten years for the Gomers. Two other African-American UB missionaries appointed during this time were sent for at least five-year terms. So there’s something there. But the Gomers’ longevity in superintending the field–over 20 years–does speak to the confidence placed in them by the UB Mission board.

By 1892, Joseph Gomer’s health was failing and he was planning to retire as mission superintendent. He and Mary had gone to Freetown with a couple who were sailing back to America. At the end of the day, wrote historian J. S. Mills, “in less than an hour Mr. Gomer was seized with apoplexy, and before medical help arrived, though delayed but a few minutes, the soul of the good man had gone to God.”

Mary Gomer stayed in Sierra Leone until 1894, and then returned to the States, where she died on December 1, 1896.

David Datema wrote of Joseph Gomer, “He was without doubt the one missionary that rescued the United Brethren mission from almost certain failure….It is doubtful whether the United Brethren have since produced a better missionary….Today in Sierra Leone, the signature work of the Gomers lives on in thousands of lives who have never heard of them.”

On August 25, 1961, Wilber L. Sites, Jr., was ordained as a United Brethren minister. The service occurred at Rhodes Grove Camp in his hometown of Chambersburg, Pa.

On August 25, 1961, Wilber L. Sites, Jr., was ordained as a United Brethren minister. The service occurred at Rhodes Grove Camp in his hometown of Chambersburg, Pa.

On Wednesday, August 22, 1980, Sierra Leone missionary teacher Jill Van Deusen couldn’t get out of bed.

On Wednesday, August 22, 1980, Sierra Leone missionary teacher Jill Van Deusen couldn’t get out of bed.