30 May On This Day in UB History: May 30 (Elmer Becker)

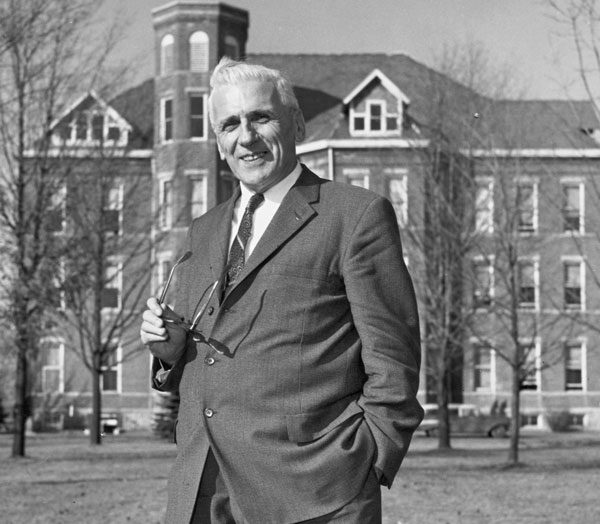

Dr. Elmer Becker in front of the Huntington University Administration Building, which is now called Becker Hall.

During its first 40 years, Huntington College went through nine different presidents. Make that eight: Clarence Mummart held the position twice–once before he was bishop, and once after.

But during the last 75+ years, there have been just five presidents. That run started with Elmer Becker, who served 1941-1965, longer than any other president before or after. He was also the last minister to fill the role. (His son, Carlson, also became a United Brethren minister.)

Elmer Becker was born May 30, 1899, on a farm near Ayr, Ontario. He became a Christian at age 17 and felt called to the ministry. He completed his high school diploma in the Huntington Academy in 1920, and graduated from the college in 1924. In 1923, he married Inez Schad, a fellow member of the debate team who, at the time, was reportedly the only female member of a college debate team in Indiana.

Becker was licensed to preach in 1924 and pastored churches in Ontario Conference for 13 years. The 1937 General Conference elected him as the denominational Secretary of Christian Education. Four years later, he became president of Huntington College. Becker’s 24-year tenure saw the addition of the Loew Alumni Library, the J. L. Brenn Hall of Science, and the Wright Hall men’s dorm, plus the expansion of the Livingston Hall dorm for women.

In 1945, Huntington College began what became a 16-year pursuit of accreditation from the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. The requirements touched nearly every aspect of the school–curriculum, faculty qualifications and salaries, buildings, tuition, administration, admissions standards, endowment, library holdings, relationships with the community, and support from the denomination. It took time and a lot of work. But on June 26, 1961, North Central called to say, “You’ve been approved.”

Before long, the entire campus was celebrating. They even rang the college bell at 10:00 a.m. President Becker was out of town, but upon returning found the faculty and staff having a picnic on his lawn. With accreditation, HC was positioned to attract more donors and students, plus better faculty.

Elmer Becker retired from the presidency in 1965 and passed away four years later.

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.  On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.

On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821.

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821. The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the

The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the