July 28, 2017

|

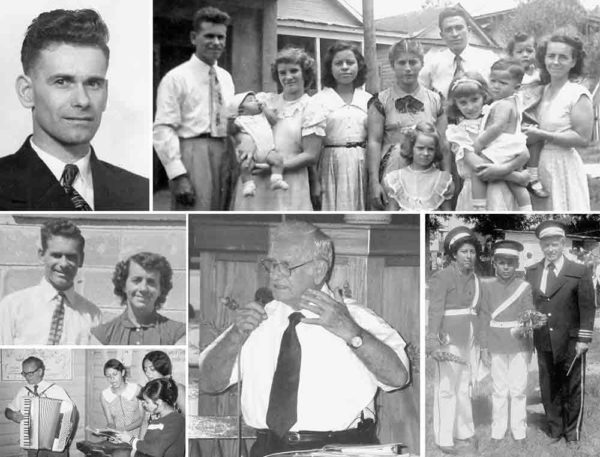

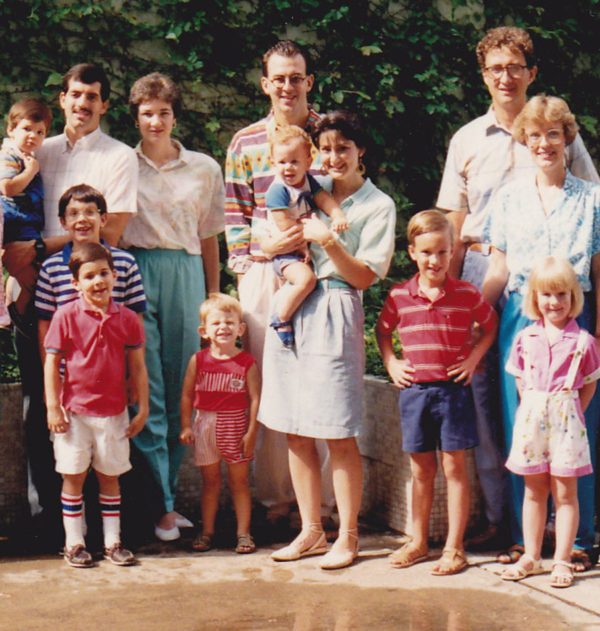

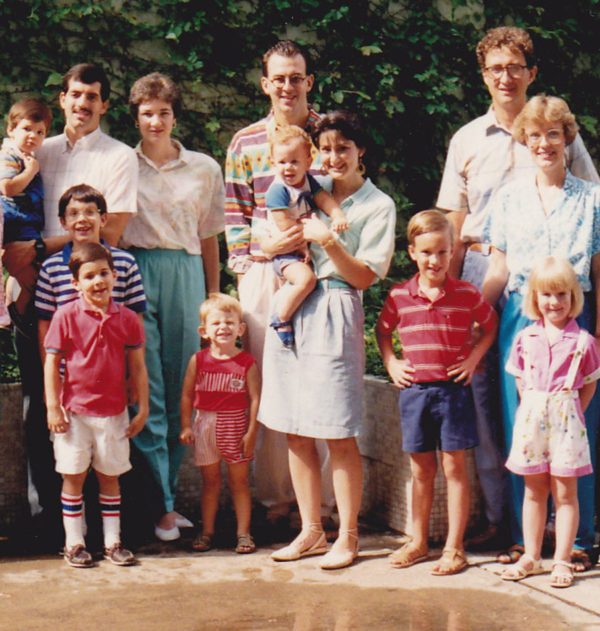

Jeff and Joan Sherlock and children (left) with the Luke and Audrey Fetters (middle) and Phil and Darlene Burkett families.

On July 28, 1990, the Sherlock family left for Macau. They thought it would be for four years.

Jeff and Joan Sherlock met at Camp Scioto, the Central Conference camp near Junction City, Ohio. Joan traveled that summer with a Huntington College singing group which ministered at Camp Scioto. Jeff, like just about everyone in his family, worked at the camp. A long-distance courtship began, and Jeff and Joan were married in July l979.

They set up home in southern Ohio, became active in the Avlon UB church in Bremen, and brought three children into the world. For 12 years, Jeff worked for a large printing company, progressing from job estimating to quality control to sales. While working fulltime, he earned a Business degree and a masters in Business Administration from Ohio University.

In 1989, as he approached the end of the MBA program, Jeff began praying about doing something more significant with his life. He said, “I was doing my job very successfully and would have become quite well off. But no matter how efficiently I made catalog inserts, there was no eternal significance. In the long term, I had nothing to gain except money.”

Then along came the Missions Impact newsletter, with an ad seeking a new missionary couple for Macau—specifically, someone with business skills. It ran for several months, and each month Jeff would think, Hmmm, they haven’t found anyone yet.

In March 1990, the Sherlocks went to Huntington, Ind., for an interview with the UB mission staff. The Board of Missions would meet March 23 to make any official appointment. But Jeff also interviewed for a teaching position at Huntington College, something he had long desired. The interview went very well. And yet, it didn’t seem right to him. Macau beckoned.

As they left the college, Jeff asked his wife, “How do you feel about this?”

He thought he knew Joan’s answer. It was a choice between living close to Joan’s family, or going to the other side of the world. A choice between the familiar and the unknown. He knew her desires, and he knew her fears. But Joan surprised him.

“I just don’t think Huntington is where we’re supposed to be right now,” she said.

And so, they sold everything and left behind their life in southern Ohio, and began ministering alongside the Fetters and Burkett families and their Chinese coworkers. Half of Jeff’s job description involved teaching in the English Language Program, and half involved finance—business manager of the mission, and treasurer of Living Water Church and the ELP.

Even before arriving in Macau, Jeff felt his financial duties should be turned over to a national. This was especially important since China would take control of Macau in 1999, and nobody knew if missionaries would still be welcome. So Jeff resolved, during his four years in Macau, to train at least one local person to handle the finances.

As it turned out, three of the first eleven members of Living Water Church were experienced in bookkeeping and finance, and the ELP’s newly-hired administrative assistant had worked ten years as assistant manager of a trading company. Jeff quickly realized finances could be turned over much sooner.

The Macau missionaries had been asking the Board of Missions for more teachers so that the pastors, Luke Fetters and Phil Burkett, could do more actual pastoring. Huntington’s response: great idea, but no money.

Jeff raised the idea of replacing his family of five with several single missionaries. As a result, by February 1993, three single missionaries were in Macau, enabling the ministry to expand in some new directions. That story was told on July 23.

The Sherlocks left Macau in December 1992, shortly after the Fetters family returned from furlough. In the words of Luke Fetters, they “accomplished more in two-and-a-half years than anyone could have expected.”