15 Oct On This Day in UB History: October 15 (Ezra Palmer)

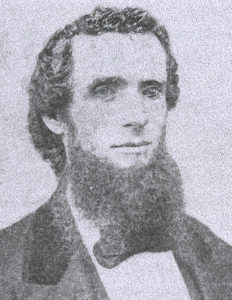

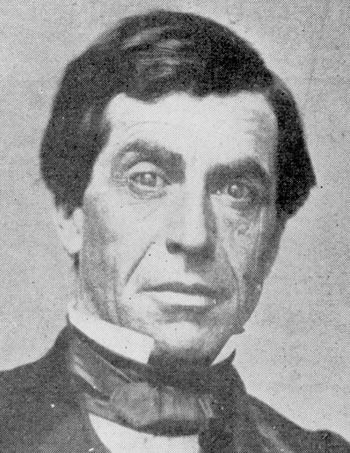

Rev. Ezra Palmer

Rev. Ezra Palmer was born October 15, 1833, in Michigan, but lived in Illinois from age 16 on. He became a United Brethren minister in 1859 and spent 30 years in the ministry. He deserves much credit for the development of what became Rock River Conference.

Ezra was first assigned to the Van Orin circuit in northern Illinois. Since he didn’t own a horse, he walked from one meeting place to another, preaching three times each Sunday, with a 15-mile walk between two of the charges. He would show up–perhaps tired, but never late–after having weathered heat, mud, snow, rain, or whatever else was required.

In 1863, Ezra married Elizabeth Carter, from Iowa. They struggled financially, especially after Ezra seriously injured his back while working in fields to bring in a little extra income.

One time Elizabeth borrowed some bread to make toast for her husband, and went without food for herself. She then found a place of solitude where, on her knees, she poured out her heart to God. As she prayed, a person from the church came by with food. But in addition to food, they needed money. So Elizabeth kept praying. The next day an elderly woman came by. “I have two dollars, and want to give you one.” In that way, God provided both food and money.

Ezra became a well-respected leader in Rock River Conference. William M. Weekley noted his “habitual prayerfulness,” his daily Scripture reading, his “renunciation of everything antagonistic to a holy life,” his love for books, and his unyielding faith. Weekley wrote, “When he spoke, the people believed him….His whole life was sacrificial. He gave himself for others.”

Ezra Palmer passed away in 1885. Elizabeth survived until 1922.

You can order most of your materials directly from manufacturers. Jane Seely (right), our Church Resources Manager, has sent customers a list of suppliers along with contact information.

You can order most of your materials directly from manufacturers. Jane Seely (right), our Church Resources Manager, has sent customers a list of suppliers along with contact information.

On October 4, 2013, Dr. Sherilyn Emberton was inaugurated as president of Huntington University. She was the first woman president in the school’s history. The installation was conducted by Ms. Kelly Savage, chairperson of the HU Board of Trustees since 2010–the first woman to chair the board.

On October 4, 2013, Dr. Sherilyn Emberton was inaugurated as president of Huntington University. She was the first woman president in the school’s history. The installation was conducted by Ms. Kelly Savage, chairperson of the HU Board of Trustees since 2010–the first woman to chair the board.