December 4, 2017

|

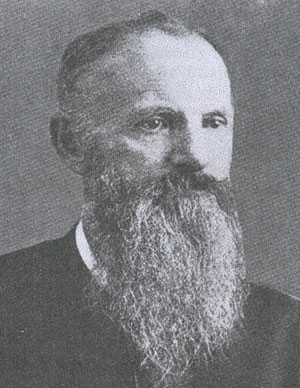

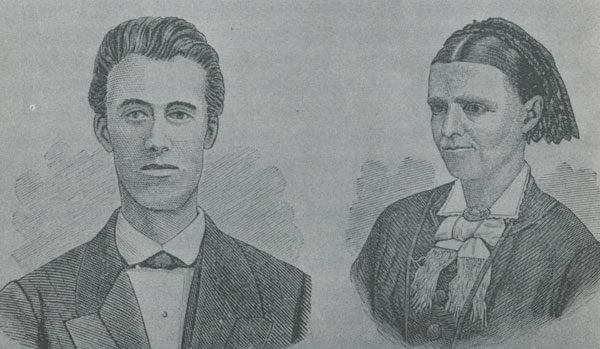

John Williams Howe

Rev. John Williams Howe was born December 4, 1829. He devoted his entire ministerial career to being an itinerant preacher in Virginia. It’s what he did. Wrote William Weekley, “From the time he joined the conference to the day of his death, he was a tireless and triumphant itinerant.”

From age 13-20, Howe was “bound out” to a farmer, and proved to be an excellent farmhand, described as “strong, willing, and industrious–but wild and reckless.” He married at age 23, and the next year was converted through the persistent witness of a friend. He immediately sensed the call to ministry. He spent a year under the direction of Jacob Markwood, then a presiding elder, and in 1858 was given his own circuit, which spanned three counties and took 200 miles to make a round.

As Howe set out on horseback for the first time, he prayed, “Lord, if just one soul is won to Christ, I will take it as evidence of your call on my life.” That first year, over 100 persons were converted.

Most meetings were held in private homes, barns, or outside. He battled snow and rain, forded swollen rivers, and sometimes got lost in the mountains. But he kept at it, year after year.

Howe is described in these ways: six feet tall, commanding presence, the “characteristic optimism of a successful general,” strong voice, a good singer, a personality “chargd like a battery with vitality,” jovial, cheerful, enthusiastic.

He weathered the Civl War years, during which his territory was a battlefield. After the war, Bishop Jacob Markwood observed, “There is nothing left of the United Brethren Church in Virginia.”

Not so fast. Weekley wrote: “John Howe was brought to the kingdom for such a time as this.” Fellow preachers may have been just as zealous, just as cultured, just as powerful in the pulpit. “But on his brow rested a crown of leadership that was readily recognized. Very speedily he was forced to the front. It is not to his discredit that he was wiling to go.”

Howe led Virginia Conference for the next 20 years as presiding elder. From the ruins of the Civil War arose a conference with 13,000 members.

He proved to be an excellent evangelist, organizer, and executive. Great revivals resulted in entire communities coming to Christ, and new churches began. He was not a general who stood behind the lines and issued orders to the troops. Rather, he was with them in the trenches, doing whatever needed to be done. And people loved him for it. It’s not surprising that he was very successful in attracting young men into the ministry.

William Weekley portrayed a man of immense gifts, who could have gone far in other careers. But instead, he gave himself entirely to the Church.

“In him we have the gospel preacher, the inspiring singer, the fervent evangelist, the wise organizer, the constructive builder, the successful financier, and the dauntless advocate of the Church with all of its institutions. It is given unto some men to possess most of these talents, but to him was given them all in an unusual degree. If his powers had been so directed, he undoubtedly would have made a notable figure in cvic life, and might have become a statesman of wide-reaching and most beneficent influence. But all his patriotism and all his knowledge of public affairs were made subordinate and tributary to the work of the ministry.”

Howe was a delegate to eight consecutive General Conferences, beginning in 1869. He opposed the new Constitution which led to the division of 1889. But when the Church adopted it, he submitted to their decision and remained a loyal churchman (rather than split off with Milton Wright).

Howe’s wife died in 1879 after 28 years of marriage. He remarried in 1890, and in the words of Weekley, “They walked together as the shadows gathered.” Howe died June 17, 1903, at age 74.

With the decision this fall to discontinue the marketing operation, Jane’s position was no longer needed. Jane saw it coming, and accepted the decision with the utmost graciousness.

With the decision this fall to discontinue the marketing operation, Jane’s position was no longer needed. Jane saw it coming, and accepted the decision with the utmost graciousness.

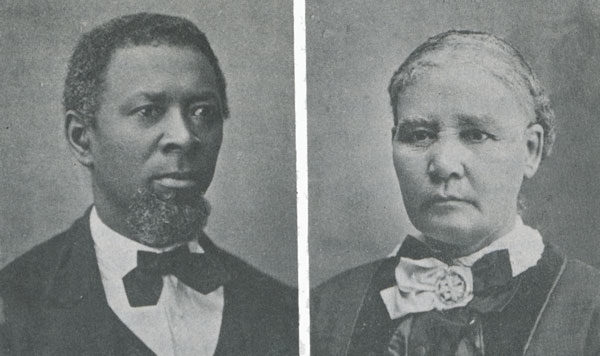

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?”

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?” During her furlough in 1983, Shirley Fretz (right) had a difficult decision to make. Her father had been hospitalized with cancer almost continuously since July 1982. Should she stay home and await his death, or return to Sierra Leone in December as scheduled?

During her furlough in 1983, Shirley Fretz (right) had a difficult decision to make. Her father had been hospitalized with cancer almost continuously since July 1982. Should she stay home and await his death, or return to Sierra Leone in December as scheduled?