27 Apr On This Day in UB History: April 27 (Susan Otterbein)

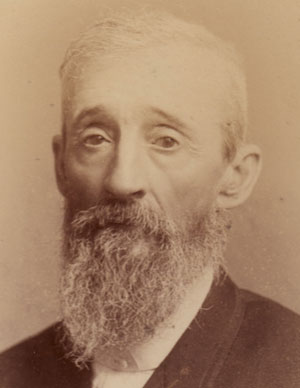

For William Otterbein, one of the United Brethren founders, six years of marriage came to an end on April 27, 1768. He was a widower at age 42, and remained single the rest of his life.

Susan LeRoy was a Huguenot, descended from French Calvinists who came to America after France outlawed Protestantism in 1685. Susan’s family arrived in Pennsylvania in 1754 and settled around Tulpehocken; the next year, an uncle was tomahawked and burned in an Indian raid. But they built homes, farmed the land, and did well.

William Otterbein was the pastor at Tulpehocken 1758-1760, so that’s undoubtedly how he and Susan met. After two years, he moved on to pastor a church in Frederick, Md. But he apparently couldn’t get Susan out of his mind. They were married on April 17, 1762. He was 36, she 26. (Different sources disagree, by a few days, on the exact date of both the marriage and Susan’s death.)

Susan joined William in Frederick, and in 1765 they took a church in York, Pa., where he spent a full nine years. It was during the second year that he traveled 25 miles east to Lancaster to attend a Great Meeting, where he met Martin Boehm and an embrace launched the United Brethren movement.

We can imagine Otterbein returning to York and excitedly telling Susan all about what had happened at Long’s Barn. Or, perhaps Susan was there to hear her husband proclaim, “We are brethren!” Maybe they used the trip to celebrate their fifth wedding anniversary. We don’t know.

What we do know is that Susan soon became afflicted with a lengthy illness. Less than a year later, she was gone.

The year of Otterbein’s marriage, a curious letter was sent to Dutch Reformed officials in Holland saying, “Brother Otterbein has entered the state of matrimony in deference to public opinion, which in America requires a minister should be a married man.” But history writers recount the great sorrow which Otterbein suffered upon the death of Susan.

Two days before he died in 1813, Otterbein asked someone to bring him a small pocketbook that Susan had made soon after their marriage 51 years before. Paul Millhouse wrote, “Those who were with him said that he kissed it with all the fondness of a youthful lover, and tears came to his eyes.”

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

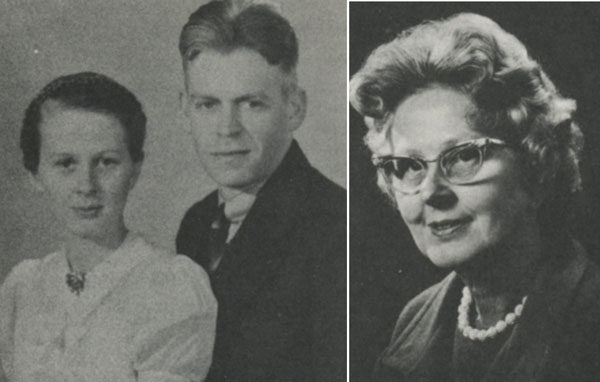

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone.

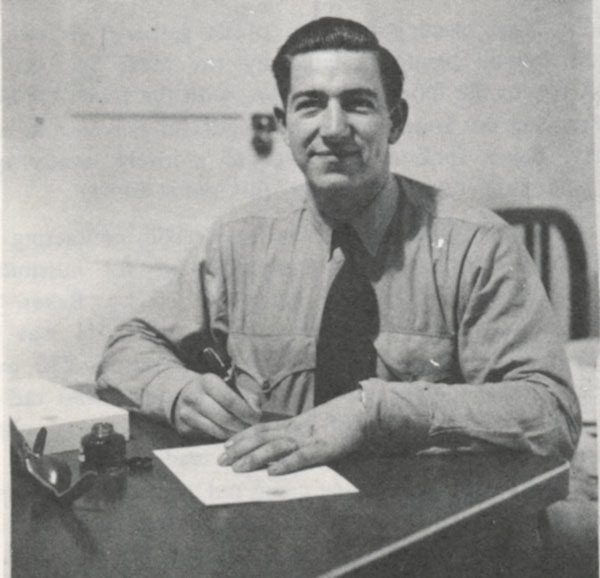

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone. On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment.

On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment. On April 17, 1948, the 24-year-old Olive Weaver began the first of what would become five terms as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She serve continuously until 1968.

On April 17, 1948, the 24-year-old Olive Weaver began the first of what would become five terms as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She serve continuously until 1968.