10 May On This Day in UB History: May 10, 1767 – The Actual Day We Began

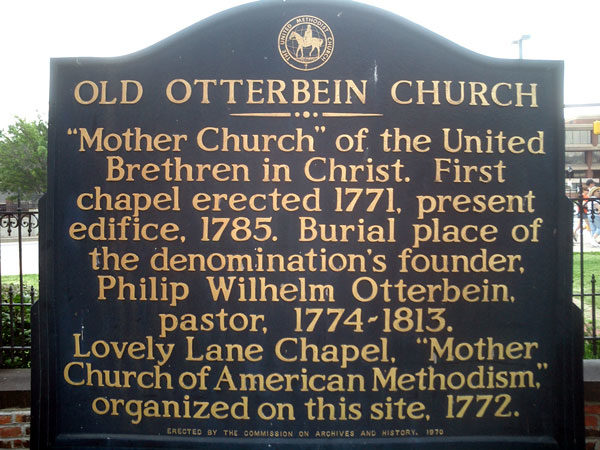

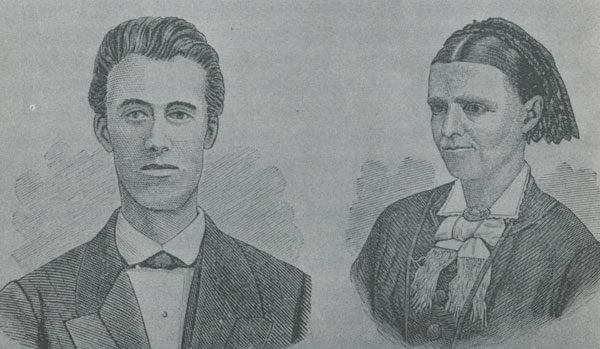

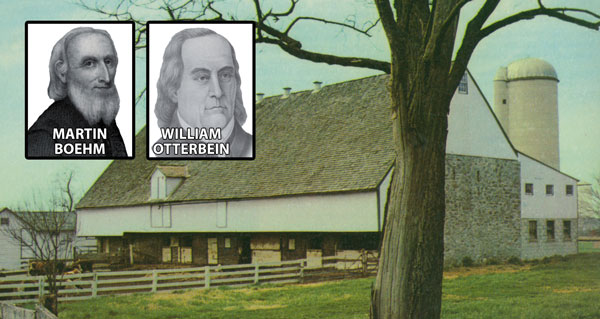

This year, 2017, the United Brethren Church celebrates its 250th anniversary. But May 10 is the exact day. On that day in 1767, our founders, Martin Boehm and William Otterbein, met in a barn in Lancaster, Pa. It was Pentecost Sunday.

“Great Meetings” dated back to the 1720s. They were usually independent religious gatherings, not connected to any particular group, and they were typically held at farms over a period of two or three days. Word would go out about an upcoming meeting—time, place, etc. People would pack up enough clothes and food to last a few days, travel however many miles they needed to travel, and bunk in homes, barns, tents, or crude shelters built just for the event. The host would stockpile food and maybe slaughter a few hogs, sheep, or even a cow. And let’s not forget the horses, who needed grain.

Various preachers would show up, gather a crowd, and let loose to everyone in hearing range. Several might be preaching at the same time on different parts of the farm—one in the barn, one under the big oak tree, one from the farmhouse porch. People from rural areas who maybe didn’t have regular access to a minister were able to sit under meaty preaching, and the fellowship was good. Probably the eating, too. Whole communities would find the Holy Spirit descending in power and changing everything.

Isaac Long, along with his brothers John and Benjamin, were among Martin Boehm’s converts among the Mennonites. All three were successful farmers. Isaac often accompanied Boehm to Great Meetings. In 1767, Isaac offered to host a Great Meeting at the barn his family had built 13 years before six miles northeast of Lancaster. How about May 10?

William Otterbein was then pastoring in York, Pa. He traveled the 30 miles to Lancaster. A minister from Virginia was preaching to an overflow crowd in the orchard. But Otterbein decided to go into the barn to hear Martin Boehm preach.

Boehm told about his conversion experience. As he plowed his fields, he knelt at the end of each row to pray, and the word “Lost! Lost!” continually hovered over him. Finally, halfway through a row, he broke. Falling to his knees, Boehm cried out, “Lord save, I am lost!” The words of Luke 19:10 immediately came to him, “I am come to seek and save that which is lost.” Joy poured through him. He ran to the house and told his wife what had happened.

The story clearly paralleled a life-changing experience Otterbein had had 22 years before when pastoring a church right there in Lancaster. He realized, “This man and I believe and have experienced the same things!”

Otterbein couldn’t contain himself. When Boehm finished preaching, Otterbein embraced him and exclaimed, “Wir sind Bruder!” We are brethren!

And thus began a lifelong friendship, and a new movement. A movement that became the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

On May 9, 1929, General Conference began at the King Street United Brethren church in Chambersburg, Pa. Beginning in 1949, General Conference would always be held in Huntington, Ind. (up through 2005). But before that, they moved around, like we do now for the US National Conference.

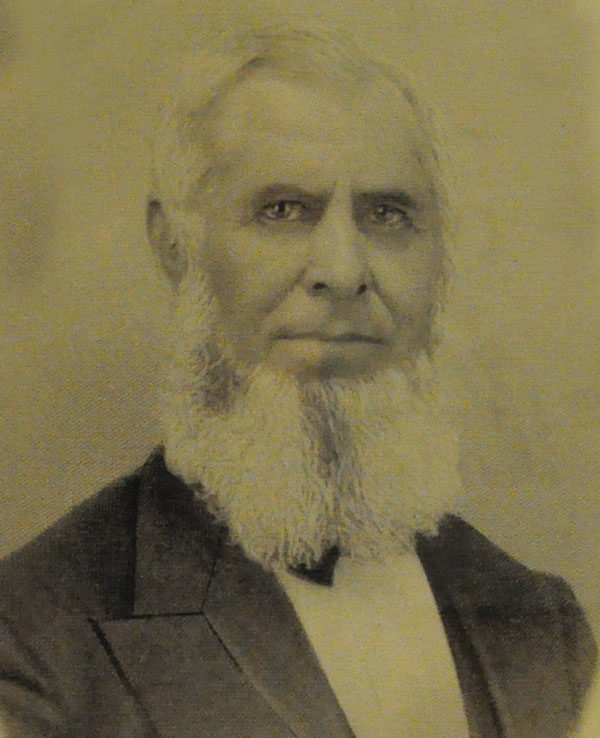

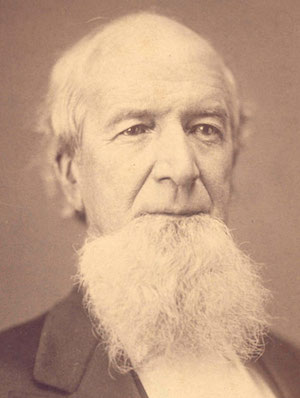

On May 9, 1929, General Conference began at the King Street United Brethren church in Chambersburg, Pa. Beginning in 1949, General Conference would always be held in Huntington, Ind. (up through 2005). But before that, they moved around, like we do now for the US National Conference. Bishop William Hanby passed away on May 7, 1880. It was written, “He was a master of the secret of growing old gracefully. No one ever heard him complain that the former times were better.” His last words: “I’m in the midst of glory.”

Bishop William Hanby passed away on May 7, 1880. It was written, “He was a master of the secret of growing old gracefully. No one ever heard him complain that the former times were better.” His last words: “I’m in the midst of glory.” Bishop Walter Musgrave passed away on May 6, 1950, in Huntington, Ind. He served 24 years as bishop, 1925-1949. Only three other bishops served longer than that. He was most know for his energetic, dynamic preaching.

Bishop Walter Musgrave passed away on May 6, 1950, in Huntington, Ind. He served 24 years as bishop, 1925-1949. Only three other bishops served longer than that. He was most know for his energetic, dynamic preaching.