May 18, 2017

|

June Brown through the years. Below:June with fellow missionary Eleanore Datema (right) at the 2009 US National Conference in Huron, Ohio.

During Commencement exercises on May 18, 1993, Huntington University recognized June Brown with the honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. The citation began, “June L. Brown has built a life of excellence everywhere she has invested her talent and energy. In education, in service to country, and in missions, she has always held to the highest standards in her personal life and professional endeavors.”

June Brown grew up in Pennsylvania; her home church was King Street UB church in Chambersburg, Pa. She accepted Christ at age eight, and at age 15 sensed God calling her to the mission field. She enrolled at Huntington University in 1948, but left to spend four years in the Women’s Air Force. While stationed in San Antonio, Texas, she taught math and science classes, and played on the base softball and basketball teams, both of which won the Women’s Air Force World Championship.

June returned to Huntington University in 1954, graduated in 1956, and became a public schoolteacher in Rockford, Ill. But the call to missions remained. In 1957, she began 35 years as a United Brethren missionary in Sierra Leone.

June’s missionary service included six years as a teacher at Centennial Secondary School, followed by 29 years at Bumpe High School, where she taught math and Bible. She also served stints as boarding home manager, bookstore clerk and acting principal, and could ably step in when the school needed an electrician, plumber, or diesel mechanic. She was renowned for her skill as a hunter.

During her furlough in 1966, June returned to Huntington College to teaching physical education and coach basketball, volleyball, and tennis. Then it was back to Africa.

In 1985, June took on the role of Director of Missionary Affairs, in addition to her regular duties in education. She remained in Sierra Leone until 1992, when all missionaries were evacuated from the country because of a military coup. She took the opportunity to retire from missionary service.

Beginning around 1973, Edward Morlai, the Sierra Leone Conference director of Church Services, worked with June Brown in the Bumpe office. He was a big fan, but by no means the only fan. He testified, “She is not a stranger; she is one of us, and we like her. She is readily accepted, not only in our church, but in our culture. We bring many problems to her, and she helps us a lot. She knows what to do at what particular time. Anywhere you go, people know Miss Brown.”

When Mr. Morlai visited the United States in 1985, he told June Brown, “Now I know what you’re giving up to come to Sierra Leone.”

June didn’t view it that way. “When I come home on furlough, I almost feel guilty being here. Everything I touch and feel and eat, everything reminds me of what I don’t have over there, and what they don’t have—and probably won’t get for years to come, no matter how hard they strive for it….I’m not giving up anything. It’s a call, a desire to do the Lord’s work.”

Mr. Morlai smiled. “I don’t think she has convinced me. It took love to leave a church like King Street and go to Sierra Leone, and stay all those years. It is a big sacrifice for her. It takes a lot of love.”

June Brown now lives in her own house in Chambersburg, and is well cared for by friends, family, and the King Street congregation.

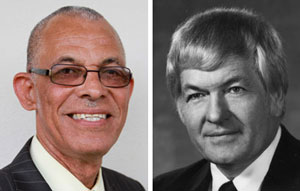

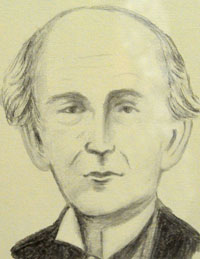

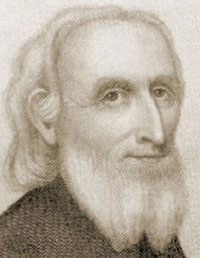

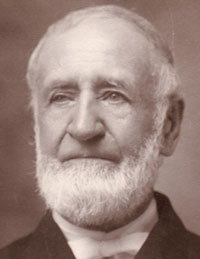

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821.

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821. The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the

The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the

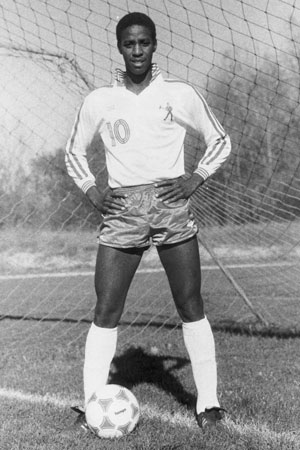

On May 14, 1988, John Buddy Labor graduated from Huntington College with a degree in Business. He was from Bumpe, Sierra Leone. His father, John Labor, was principal of Bumpe High school and a longtime leader in Sierra Leone Conference.

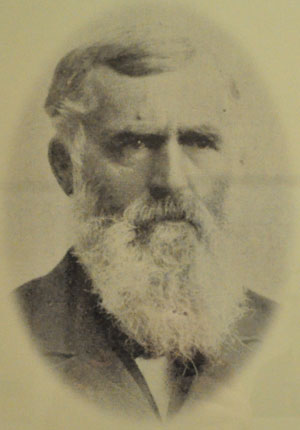

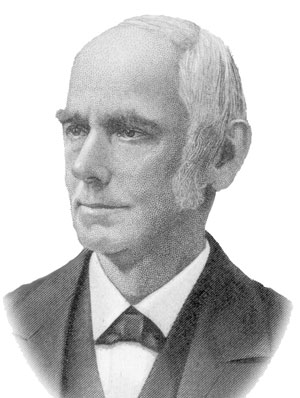

On May 14, 1988, John Buddy Labor graduated from Huntington College with a degree in Business. He was from Bumpe, Sierra Leone. His father, John Labor, was principal of Bumpe High school and a longtime leader in Sierra Leone Conference. On May 13, 1889–Day Four of General Conference–Bishop Milton Wright (right) and 14 other delegates walked out. They’d had enough. Time to start a new denomination.

On May 13, 1889–Day Four of General Conference–Bishop Milton Wright (right) and 14 other delegates walked out. They’d had enough. Time to start a new denomination. The entire Civil War occurred between the General Conferences of 1861 and 1865.

The entire Civil War occurred between the General Conferences of 1861 and 1865.