02 Jun On This Day in UB History: June 2 (Olin Alwood and Harold Mason)

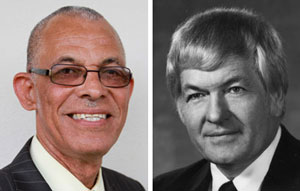

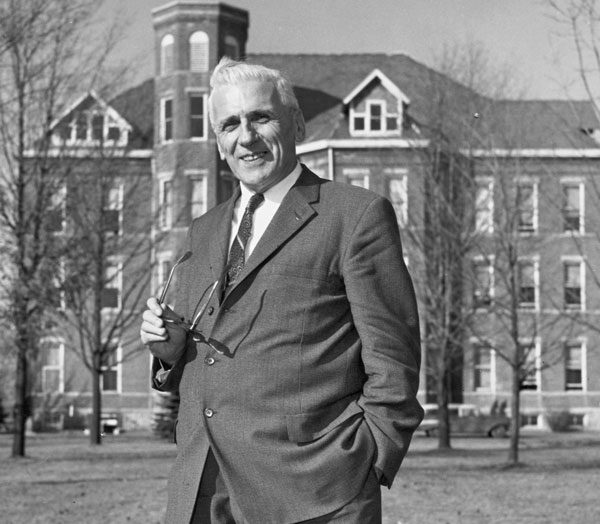

Olin Alwood (left) and Harold Mason.

Two bishops passed away on June 2–Olin Alwood in 1945, and Harold Mason in 1964. Both completed their careers outside of the United Brethren Church.

Olin Alwood served 16 years as bishop, 1905-1921. However, it’s his father, Rev. J. K. Alwood, that we remember. J. K. wrote the hymn, “The Unclouded Day.”

Olin Alwood, born in 1870, attended Hartsville College, a United Brethren school in southern Indiana, and dedicated his life to Christ there in 1889. After teaching school for three years in Nebraska, he became a licensed United Brethren minister and was assigned to the Sugar Grove circuit near Camden, Mich. He went on to serve several other circuits in Ohio and Michigan, and by 1903 had become the presiding elder in North Ohio Conference.

At the time, we had four bishops, three of whom retired in 1905. Alwood, 34, was among the new bishops elected that year. After 16 years as bishop, serving a different district every four years, he became editor of the denominational paper, The Christian Conservator. He apparently found that job frustrating. He stepped down from that role in 1925 and said no to being re-elected as bishop.

In 1927, Alwood transferred into the “other” United Brethren Church. He pastored several churches with them until passing away suddenly in 1945.

Harold Mason graduated from Huntington College in 1907 (called Central College back then) and was assigned to a church circuit in Hillsdale County, Mich. It went badly. After a year, the boy preacher left the ministry for a few years. But he regained a sense of calling to the ministry and plunged back in. The result: eight very successful years at two churches–in Blissfield, Mich., and Montpelier, Ohio.

That success got him elected bishop in 1921. He served four years, and that was apparently enough. The rest of his life was devoted mostly to higher education–four years at Adrian College as a professor and academic dean, three years as superintendent of schools in Blissfield, seven years as as president of Huntington College (1932-1939), Professor of Christian Education at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, and from 1948-1961, chairman of the Department of Christian Education at Asbury Theological Seminary. He passed away on June 2, 1964.

On June 1, 1854, the newly-created United Brethren mission board–the Home, Frontier, and Foreign Missionary Society–met in Westerville, Ohio. Their first action was a big one: “Resolved, That we send one or more missionaries to Africa as soon as practicable.”

On June 1, 1854, the newly-created United Brethren mission board–the Home, Frontier, and Foreign Missionary Society–met in Westerville, Ohio. Their first action was a big one: “Resolved, That we send one or more missionaries to Africa as soon as practicable.”

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.  On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.

On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.