30 Apr On This Day in UB History: April 30 (Pelley Murders)

From upper left: Jeff Pelley in 2006; the Pelley family (the four victims are in front); the Olive Branch parsonage.

On April 30, 1989, Pastor Robert Pelley didn’t show up for church at Olive Branch UB in Lakeville, Ind. (just south of South Bend). Eventually, two men went next door to the parsonage. They knocked several times, but got no response. The blinds were tightly drawn.

The found a spare key, entered the house…and discovered a grisly scene. Robert Pelley (38), lay dead in the upstairs hallway, killed with two deer slugs. In the basement were wife Dawn (32) and her two youngest daughters from a previous marriage, Janel (8) and Jolene (6). All had been shot in the head. Three children were not at home: Robert’s son Jeff and his sister Jacqueline, from a previous marriage, and Dawn’s daughter Jessica, 9. (Both Robert and Dawn were widows.)

Jeff Pelley, a 17-year-old high school senior, was always the leading suspect, but wasn’t arrested or charged. There just wasn’t sufficient evidence. He moved to Florida, developed a good career, married, had a child, and was teaching Sunday school.

Thirteen years passed. Then a Cold Case squad reopened the investigation. Jeff Pelley was arrested in August 2002 and charged with the four murders. In July 2006, he went on trial.

The evidence was very circumstantial. No murder weapon was ever found (Bob’s 20 gauge Mossberg was never located). No fingerprints linked Pelley to the crime itself. Rather, the prosecution relied on a carefully constructed timeline which put Jeff Pelley at the parsonage during a particular 20-minute period, during which he did a whole bunch of things (commit the murders, change clothes, load the washing machine, take a shower, locate and pick up the shell casings, draw the blinds, lock the doors, get rid of the gun and casings, and more).

Investigators said he was angry at his father for grounding him from attending pre- and post-prom activities, and from driving his car. After the killings, they said, he cleaned up, went to the prom with his girlfriend, stayed overnight with friends, and the next day went with friends to the Great America theme park in Chicago, where he was located on Sunday.

During the trial, Jeff Pelley’s attorneys insisted there wasn’t enough time for him to kill his family, do everything they claimed he did, and still make it to the prom, and that after committing an act like that, nobody would act normal, which is how friends testified that he acted during the prom events.

After a six-day trial which included nearly 40 witnesses, jurors deliberated for 34 hours and returned a guilty verdict. Pelley, now 34 years old, was sentenced to 160 years in prison (four consecutive 40-year sentences). A Court of Appeals reversed the conviction in 2008, but in 2009 the Indiana Supreme Court upheld the conviction. He is now incarcerated at the Wabash Correctional Facility near Terra Haute, Ind.

A book about the case, The Prom Night Murders, was published in 2009. A lengthy article appears here.

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

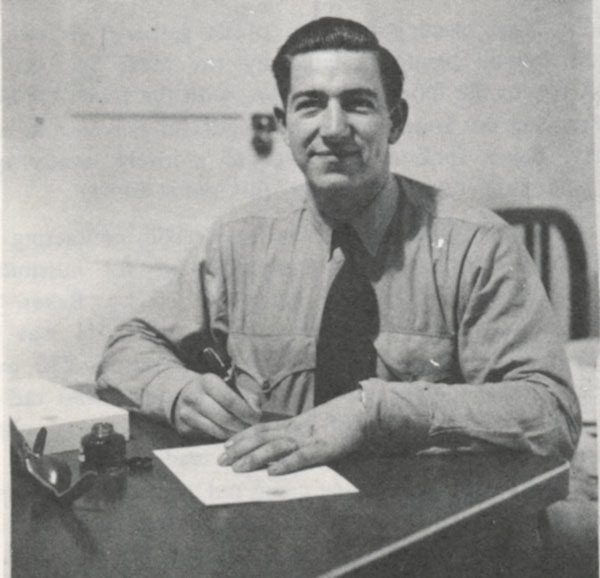

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone.

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone. On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment.

On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment.