April 8, 2017

|

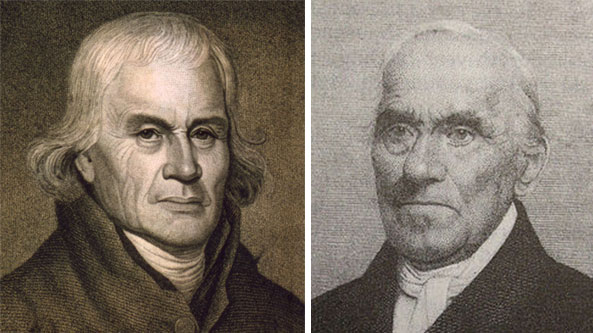

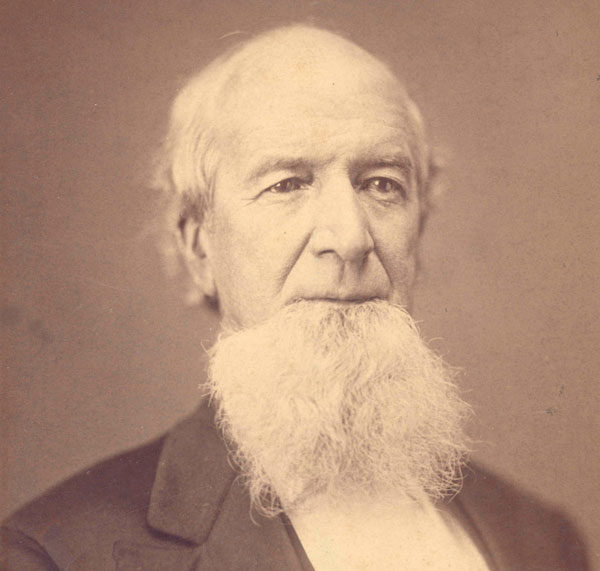

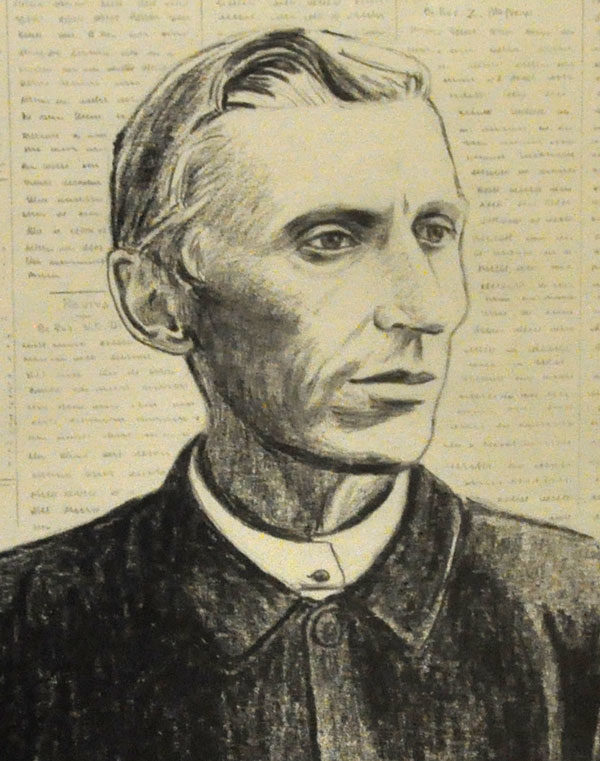

Bishop William Hanby

William Hanby was born in western Pennsylvania on April 8, 1808. For a period of over 20 years, Hanby–quite illegally–helped a whole bunch of fugitive slaves evade capture and escape to frreedom. He also found time to be bishop for four years, edit the denominational paper for 12 years, and help start the first United Brethren college.

A childhood experience probably sensitized Hanby to the plight of slaves. At age 16, he decided to become a saddler–a person who made and repaired saddles and harnesses. To learn the trade, he signed a legal contract to become an indentured servant to Jacob Good. The guy turned out to be a cruel, abusive scoundrel. One time, according to biographer Henry Adams Thompson, young William almost died under Good’s punishment.

Three years into the five-year contract, William had had enough. Late one night in 1828, he escaped out a second-story window and headed for Ohio, traveling by night lest he be caught by his wrathful master, who had repeatedly promised to “follow me to hell.” Pennsylvania law made Hanby no better than a runaway slave.

In Zanesville, Ohio, a godly family took him in. He became a Christian, and began plying his trade as a saddler (which he plied for most of his life). But he knew he needed to make things right with Jacob Good. Hanby traveled to Pennsylvania with all the money he had saved, settled things with Good, and returned to Ohio–broke, but happy.

That same year, 1830, Hanby sensed God calling him into the ministry. The United Brethren church licensed him to preach in April 1831, and two years later he was assigned to a circuit of 28 appointments. It took him four weeks to travel the 170-mile route. But he wasn’t a pastor for very long.

From 1837-1845, Hanby was editor of the denominational paper, The Religious Telescope, working out of Circleville, Ohio. As editor, he wrote strongly against slavery. He also practiced what he preached.

Hanby actively helped fugitive slaves coming up from Ohio and other Southern states–even though such aid was illegal in Ohio, punishable by heavy fines and imprisonment. He and a local merchant named Doddridge established a station on the underground railroad. Many times, Hanby would be called away late at night to assist runaway slaves, often sheltering them in his barn and saddlery shop, or helping them continue on toward Canada.

One time, Doddridge showed up at midnight saying he was hiding five slaves, and their pursuers were close behind. Hanby helped transport the slaves to another home, where they were buried under hay. The pursuers searched that home, and even walked over the hay, but left without finding the fugitives. One of those slaves later made five more trips into the South to bring back his mother, then his wife, and then some of his children. All, with Hanby’s help, reached freedom in Canada.

It was risky, dangerous stuff for Hanby, and you can question the idea of a denominational official intentionally breaking the law. But he argued, “We may be bound by a man-made law, but we are more bound by a Lord-given conscience.” Perhaps he was molded by his own experience of virtual slavery, and the abuse and injustice he had suffered under his own white master, Jacob Good.

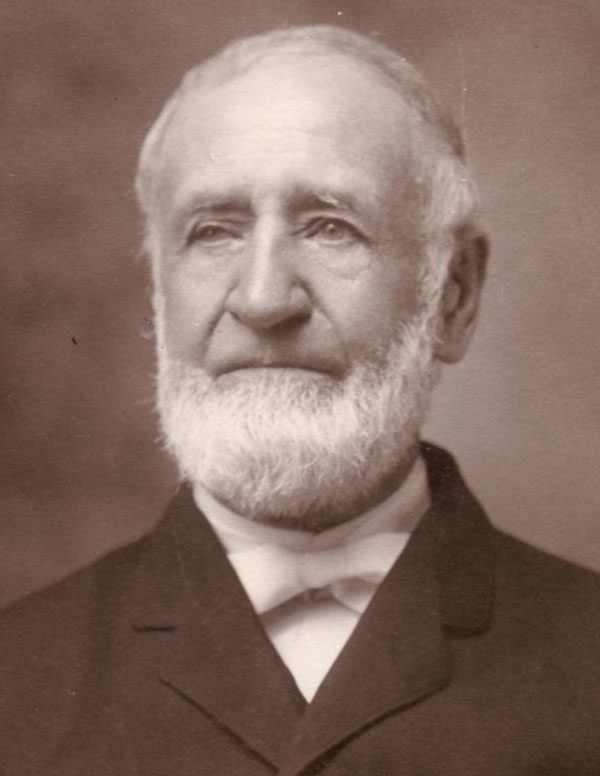

William Hanby served 1845-1849 as bishop, spent the next four years again editing the magazine, and in 1853 became a cofounder of Otterbein University, which is where he focused the rest of his life. Otterbein University became known as a stop along the Underground Railroad. University president (and future bishop) Lewis Davis was also involved in aiding and sheltering fugitive slaves.

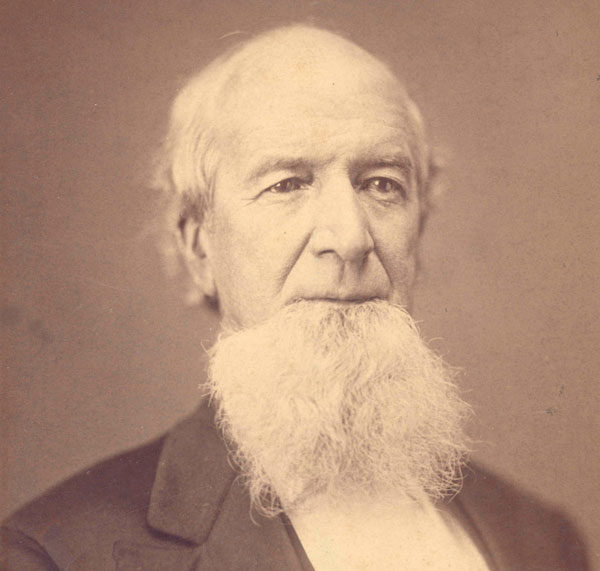

So was son Benjamin Hanby. In 1856, Benjamin wrote the song “Darling Nelly Gray” from the point of view of a Kentucky slave whose sweetheart has been sold to new masters in Georgia. It was based on an actual slave, Joseph Selby, who died at the Hanby home while trying to reach Canada. William raised money to try to free the woman. (Benjamin also wrote the Christmas songs “Jolly Old Saint Nicholas” and “Up on the Housetop.”)

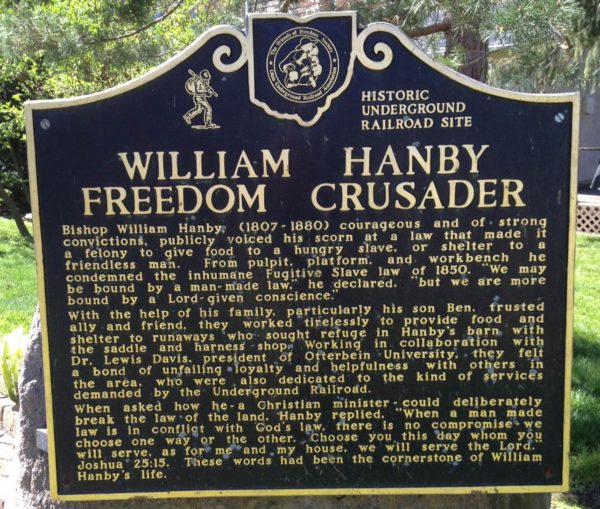

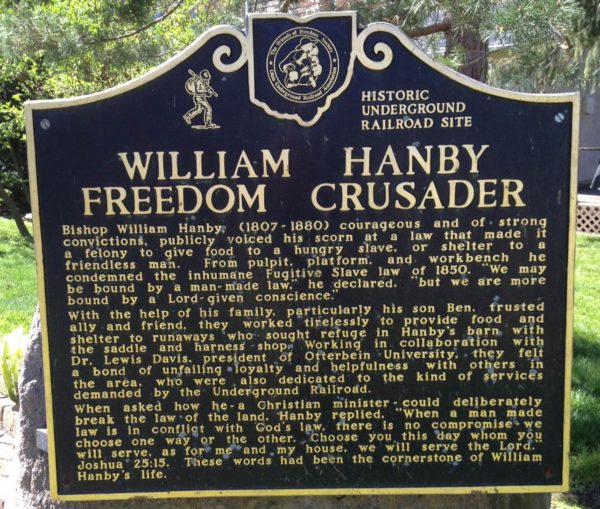

Today, the Hanby House at Otterbein University commemorates the courageous humanitarian actions of this United Brethren bishop. A historical marker hails him as a “Freedom Crusader.”

In 1978, two UB missionaries in Sierra Leone, Shirley Fretz and nurse Beverly Glover, were involved in an auto accident in which an African man was killed. Manslaughter charges were filed against Shirley and the driver. The ensuing legal ordeal dragged on for nearly a year.

In 1978, two UB missionaries in Sierra Leone, Shirley Fretz and nurse Beverly Glover, were involved in an auto accident in which an African man was killed. Manslaughter charges were filed against Shirley and the driver. The ensuing legal ordeal dragged on for nearly a year.

The Jerry Datema family moved to Jamaica in 1964, after having served in Sierra Leone 1957-1963. Datema (right) became field superintendent, following founder James O’Sullivan.

The Jerry Datema family moved to Jamaica in 1964, after having served in Sierra Leone 1957-1963. Datema (right) became field superintendent, following founder James O’Sullivan.