28 Apr On This Day in UB History: April 28 (The Hadleys)

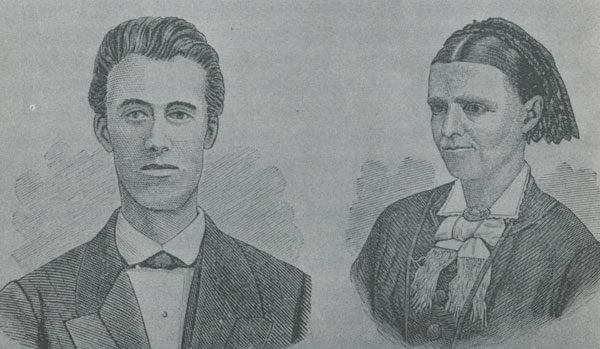

Oliver and Mahala Hadley, missionaries to Sierra Leone, 1866-1869

No missionaries suffered more than Rev. Oliver and Mahala Hadley. That was the opinion of Amanda Billheimer, one of the first United Brethren missionaries to Sierra Leone, as she reviewed the first 50 years of UB mission work. She wrote, “I believe no truer servants of God ever went out to do His bidding in any non-Christian land.”

The Hadleys served in Sierra Leone 1866-1869. They were the first to leave a child at home—14-month-old Mary Elizabeth, left in the care of her grandmother in Indiana. They were the first to lose a child in Africa. And Mrs. Hadley was the first to lose a spouse as a result of serving Christ in Sierra Leone.

Oliver and Mahala, the daughter of a UB minister, were married in 1864. Two years later, they sailed for Sierra Leone, arriving on December 13, 1866, after a 51-day voyage.

Oliver fought sickness throughout their term, and Mahala watched her husband’s health deteriorate during those two years. Nevertheless, Oliver threw himself into the work. He kept a journal. His first entry of 1867, written on January 3, said, “Oh, when shall I see some of these men converted? I cannot rest until I hear some of them glorify God for the salvation of their souls. The Gospel is the power of God, and I look for a manifestation of that power here.”

A baby girl was born in April 1867. They named her Ida. Six weeks later, during the night, they watched helplessly as she died. Mahala later wrote, “We were alone and far from all Christian friends. There was no minister on whom we could call, and no one to offer a word of comfort. Our tears fell thick and fast. I prayed while my husband tried to conduct the funeral service himself. God seemed near to us in our sadness, and with our own hands, we laid our baby in a grave under the trees in the mission compound.”

At the end of December 1868, Oliver became very sick. He wrote of a violent cough, nausea, diarrhea, lack of appetite, and serious back pain. Yet, he kept a positive attitude. He wrote on December 29, “I have set my face to seek to be profited by everything that befalls me. I have been profited. I have a sweet peace.”

He added, “I am often so distressed at the thought that I can do so little, if anything, toward the salvation of these people.”

Another child, a son, was born January 17, 1869, after what Oliver described as a remarkably easy childbirth. At that point, they were preparing to leave Africa. Their ship departed Freetown on March 1, bound for Boston. The captain’s cabin was the only heated room on the ship. Seeing the Hadleys’ physical plight, the captain gave them his cabin for the journey. The Hadleys reached America on April 15 and continued on to their home near Lafayette, Ind.

On April 28, Oliver died. He was 31 years old. Ten days later, their infant son died.

Eighteen months later, in December 1871, Mahala Hadley returned to Sierra Leone and served another three years. They were good years; the mission was finally experiencing the success for which her husband had yearned. George Fleming, a former mission director, wrote, “She was favored by the mercies of her Heavenly Father to taste the sweetness of victory after experiencing round after round of disappointment and tears.”

Oliver Hadley was our Jim Elliott, the missionary slain by Auca Indians in Peru in 1956. There are many similarities. Both were young, had an infant daughter, and carried a passion for unreached tribal people. Both died while just getting started, never seeing the fruit of his efforts. Both had a wife—Mahala Hadley and Elizabeth Elliott—who returned to the field for a few years and experienced the joy of seeing her late husband’s hopes and prayers fulfilled. And both left behind an incredible journal.

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

In 1889, the year of the division in our denomination, we elected four bishops. Three of them–Milton Wright, Halleck Floyd, and Horace Barnaby–served together for the next 16 years. All three left office in 1905. And all three died in 1917.

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone.

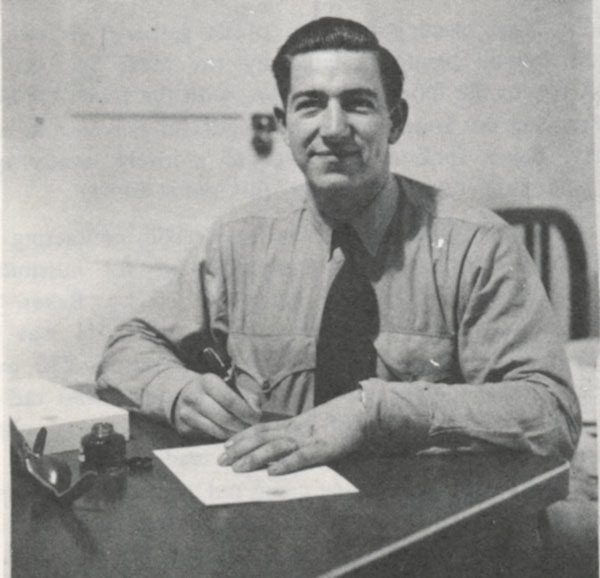

On April 19, 1929, Ellen Rush (right) concluded six years as a missionary in Sierra Leone. On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment.

On April 18, 1925, Clarence Carlson boarded a ship for Sierra Leone. He would go on to serve five terms as a missionary, pastor UB churches in three different states, and spend eight years as bishop. But at this point, he was just a 28-year-old Huntington College drop-out embarking on his first ministry assignment. On April 17, 1948, the 24-year-old Olive Weaver began the first of what would become five terms as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She serve continuously until 1968.

On April 17, 1948, the 24-year-old Olive Weaver began the first of what would become five terms as a missionary in Sierra Leone. She serve continuously until 1968.