01 Apr On This Day in UB History: April 1

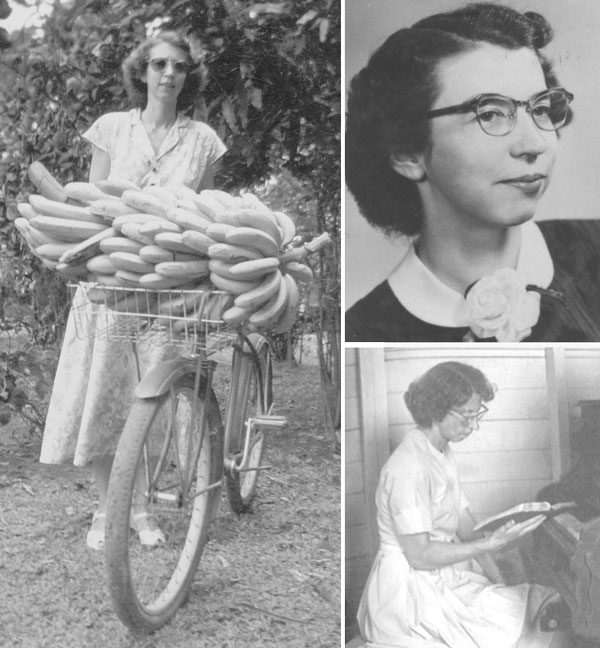

Betty Brown, 22 years in Honduras

On April 1, 1950, Betty Brown boarded a ship in New Orleans. Two days before, her best friend at Huntington College, Juanita Smith, had arrived in Sierra Leone to begin what would be 15 years as a UB missionary nurse. Betty was headed in a different direction–to Honduras, where she would spend the next 22 years. That’s longer than any other missionaries to Honduras except for the Archie Cameron family.

Betty was one of those silent saints whom history can easily overlook, but who, during their years walking the earth, leave a trail of goodness and light. Said Archie Cameron: “I always characterized her as a person who really lived, ‘I am crucified with Christ.’ Everybody saw Betty as a godly woman. She did all the little things that no one else would do, and was always there to help in every way.”

Betty came to Honduras as a trained schoolteacher, but after the school closed, she found many other valuable ways to serve—working with children and youth, training Sunday school teachers, organizing Vacation Bible Schools, directing children’s programs, leading the Honduras Women’s Missionary Association, helping with music, and so much more. She planned the flannelgraph lessons given in villages, and kept everything organized so she knew which lessons had been given in which villages, and which lesson needed to come next so they could systematically go through the Bible.

She also poured her life into a small group of girls, organizing a three-year training program with the goal of developing them into godly women. She taught them during the week—child psychology, techniques for working with different age groups, how to craft an effective Bible lesson—and on weekends took them to villages to minister in homes and churches.

“As far as missionaries went, she was the best you could find,” said Reina Velez, one of those girls.

Missionary Leora Ackerman: “You talk to any of her former students and they’ll say, ‘Oh, Miss Betty was special.’ She was a wonderful, wonderful Christian girl. Solid. The teachers loved her, and the students loved her, too. We loved her; our kids still call her Aunt Betty.”

Archie Cameron: “Her contribution was great. She ran the school well, she trained those girls well, she worked in the bookstore well, she worked well with young people and children. She was professional in everything she did—it had to be done correctly. But she was always in the background. Her greatest contribution was just all the little things that she did.”

Missionary Vernon Macy: “There wasn’t anything too great or too small for her to do. She was a tremendous person.”

Archie: “Betty was the kind of person who did little thoughtful things for people, things that other persons wouldn’t do. She would wrap up a bottle of Coke to give somebody for a birthday. I wouldn’t do that because that’s too small, but it wasn’t too small for Betty. And can you imagine how much that person appreciated receiving the bottle of Coke? That was Betty all the way through.”

Betty did many things well and with high professionalism. But most importantly, everybody could see that Betty Brown walked with God. “Just being here,” said Archie, “she was valuable.”

Betty finally left Honduras 1972 to take care of her elderly father and stepmother. She passed away on April 19, 1987. Easter Sunday.

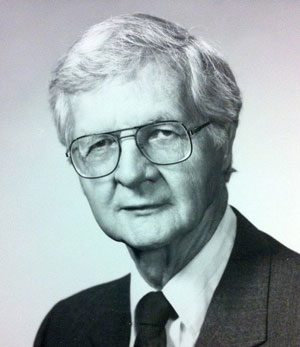

Dr. J. Edward Roush passed away on March 26, 2004. He was 83. Roush served eight terms as a US Congressman from northern Indiana, and was instrumental in establishing the 911 emergency phone system. Roush was deeply committed to the United Brethren church and to Huntington University. He and his wife, Polly, were longtime members of College Park UB church in Huntington, Ind.

Dr. J. Edward Roush passed away on March 26, 2004. He was 83. Roush served eight terms as a US Congressman from northern Indiana, and was instrumental in establishing the 911 emergency phone system. Roush was deeply committed to the United Brethren church and to Huntington University. He and his wife, Polly, were longtime members of College Park UB church in Huntington, Ind.

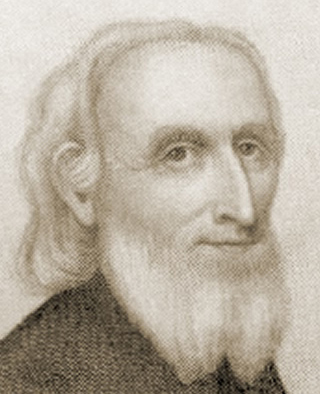

Martin Boehm, one of the two founders of the United Brethren Church, passed away on March 23, 1812. It seemed to have been somewhat unexpected; he had enjoyed good health, and was riding short distances on horseback until a few days before his death. But when it came, it came fast, with increasing weakness and debility.

Martin Boehm, one of the two founders of the United Brethren Church, passed away on March 23, 1812. It seemed to have been somewhat unexpected; he had enjoyed good health, and was riding short distances on horseback until a few days before his death. But when it came, it came fast, with increasing weakness and debility.

Duane Reahm retired in 1981 after 12 years as bishop. He had given 22 years as a United Brethren pastor, and 20 years as a denominational official–eight years as Director of Missions, four years as Bishop of the East District, and eight years as Overseas Bishop.

Duane Reahm retired in 1981 after 12 years as bishop. He had given 22 years as a United Brethren pastor, and 20 years as a denominational official–eight years as Director of Missions, four years as Bishop of the East District, and eight years as Overseas Bishop.

Robert Rash was born March 16, 1904. He would go on to serve 43 years as a United Brethren minister. He started and pastored a number of churches, and served 24 years at the national office–16 years as Director of Christian Education, and eight years as bishop. He was a marvelous servant of the Church–a godly man able to do a lot of things well.

Robert Rash was born March 16, 1904. He would go on to serve 43 years as a United Brethren minister. He started and pastored a number of churches, and served 24 years at the national office–16 years as Director of Christian Education, and eight years as bishop. He was a marvelous servant of the Church–a godly man able to do a lot of things well.