11 May On This Day in UB History: May 11 (Civil War)

The entire Civil War occurred between the General Conferences of 1861 and 1865.

The entire Civil War occurred between the General Conferences of 1861 and 1865.

Almost all UB members in Virginia opposed slavery, but were basically cut off from the rest of the denomination. When the war started, some UBs suggested going independent and forming a southern United Brethren church.

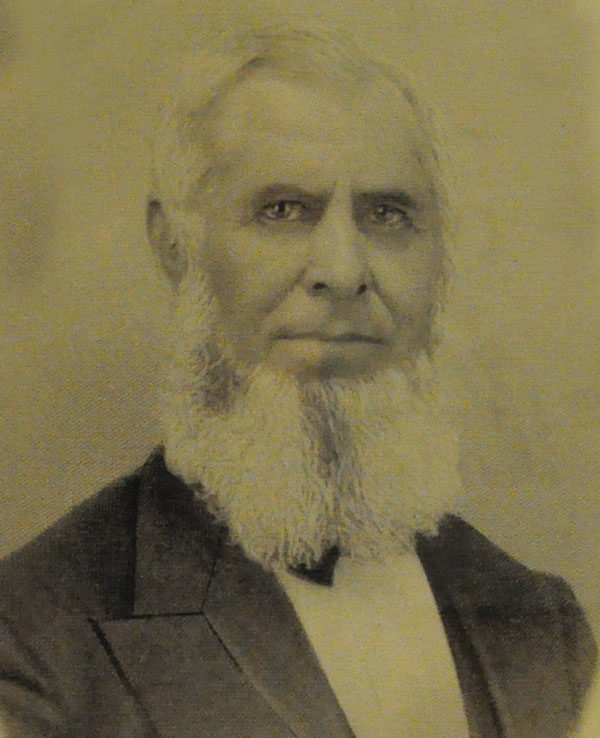

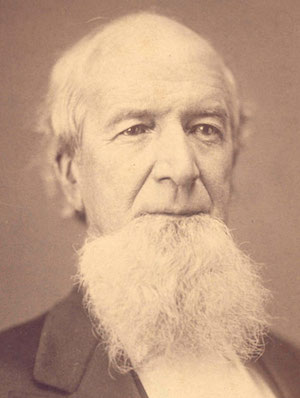

However, Bishop Jacob John Glossbrenner (right) decided to stay in Virginia throughout the war, and he was the glue. The Maryland and Virginia churches, part of the same conference, held separate annual conferences for the duration. Glossbrenner was allowed to pass through the battle lines to hold conference for the Maryland churches and then return to Virginia.

The 1865 General Conference met May 11, 1865, in Iowa. By that time, the war had been over for a month. However, on May 10, Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, was finally captured in Georgia. When this news reached the conference, there was much rejoicing and they broke out in the “Doxology.”

Bishop Glossbrenner was there. Some ministers initially treated him coldly, suspicious of his decision to spend the war in Confederate territory. But after hearing Glossbrenner’s story, delegates passed a resolution commending his heroic leadership of the Virginia churches during the war.

The Civil War, which United Brethren people generally viewed as a just war to end a great evil, prompted us to reconsider our 1849 statement which emphasized pacifism. The 1865 General Conference, while still opposing aggressive warfare, added, “We believe it to be entirely consistent with the spirit of Christianity to bear arms when called upon to do so by the properly constituted authorities of our government for its preservation and defense.”

By 1865, Glossbrenner had already served 20 years as bishop. He continued another 20 years. His 40 years as bishop is longer than any other bishop, ever. He died two years after leaving office, possibly of stomach cancer.

On May 9, 1929, General Conference began at the King Street United Brethren church in Chambersburg, Pa. Beginning in 1949, General Conference would always be held in Huntington, Ind. (up through 2005). But before that, they moved around, like we do now for the US National Conference.

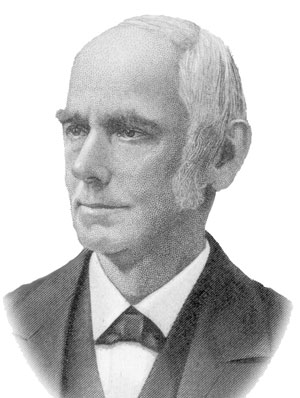

On May 9, 1929, General Conference began at the King Street United Brethren church in Chambersburg, Pa. Beginning in 1949, General Conference would always be held in Huntington, Ind. (up through 2005). But before that, they moved around, like we do now for the US National Conference. Bishop William Hanby passed away on May 7, 1880. It was written, “He was a master of the secret of growing old gracefully. No one ever heard him complain that the former times were better.” His last words: “I’m in the midst of glory.”

Bishop William Hanby passed away on May 7, 1880. It was written, “He was a master of the secret of growing old gracefully. No one ever heard him complain that the former times were better.” His last words: “I’m in the midst of glory.” Bishop Walter Musgrave passed away on May 6, 1950, in Huntington, Ind. He served 24 years as bishop, 1925-1949. Only three other bishops served longer than that. He was most know for his energetic, dynamic preaching.

Bishop Walter Musgrave passed away on May 6, 1950, in Huntington, Ind. He served 24 years as bishop, 1925-1949. Only three other bishops served longer than that. He was most know for his energetic, dynamic preaching.