13 Mar On This Day in UB History: March 13 (Dr. William Witte)

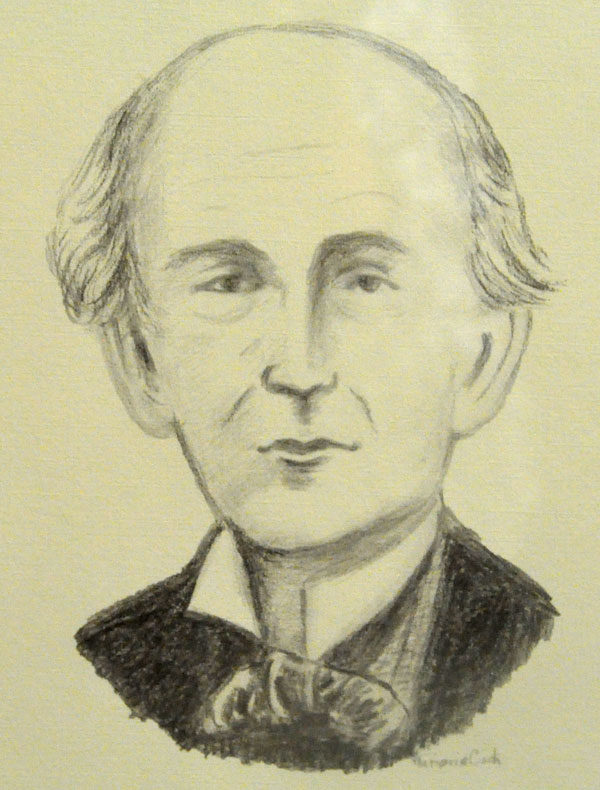

Dr. William B. Witte in his Civil War uniform.

In 1856, we appointed our first two missionaries to Sierra Leone: Rev. J. K. Billheimer of Virginia, and Dr. William B. Witt of Cincinnati. They sailed from New York City on December 5, 1856, and arrived in Sierra Leone about 40 days later.

Dr. Witt served 18 months before illness forced him to leave Africa. Mission director Daniel Flickinger said he provided valuable, fruitful service to people both spiritually and physically, “being well skilled in the science of medicine, a fluent preacher, and a warm-hearted Christian.”

Four years after returning to the States, Witt entered the Civil War as a physician with the 69th Indiana Infantry Regiment. The regiment formed with about 1000 troops on August 19, 1862, and ten days later suffered 218 casualties in the disastrous Union defeat at Richmond, Kent. The entire regiment was captured. After going through a prisoner exchange, they reorganized at the end of November. The 69th Indiana went on to participate in numerous battles, including Chickasaw Bayou, Milliken’s Bend, Port Gibson, Champion’s Hill, and Vicksburg.

Witt died on March 13, 1864 on the Gulf Coast of Texas. The regiment was moving from its inland camp at Indianola to Matagorda Island. That required crossing a 300-yard stretch of Matagorda Bay in a makeshift raft consisting of pontoon boats tied together.

As Witt’s group crossed, carrying full equipment, an incoming wave swamped the raft. Witt–doctor, minister, missionary, soldier–was among the 23 men who drowned.

Throughout 2017, as we celebrate the United Brethren denomination’s 250th anniversary, we are looking at events throughout our history.

Throughout 2017, as we celebrate the United Brethren denomination’s 250th anniversary, we are looking at events throughout our history.