November 4, 2017

|

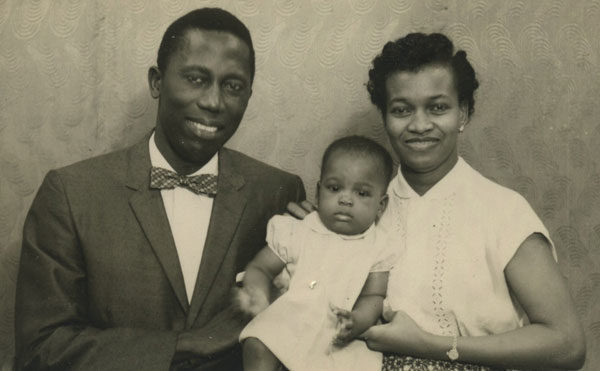

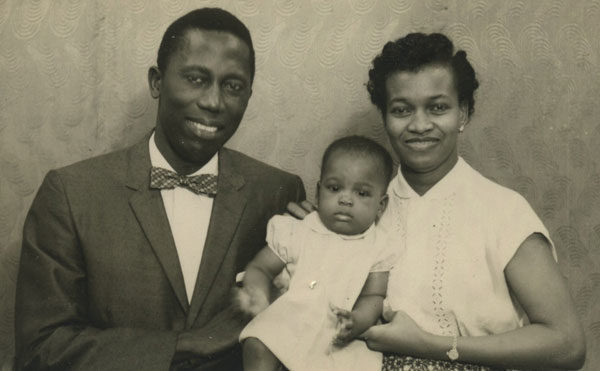

Dr. Sylvester and Dorothy Pratt with their first child, Melody.

In 1946, the Missions board decided to open a full-fledged hospital in Mattru Jong, Sierra Leone. It would replace the medical dispensary which had operated in Gbangbaia since 1914. A hospital, of course, would require a doctor. They figured that would be Dr. Leslie Huntley, who had served eight years at Gbangbaia in the 1930s. But that didn’t happen. Instead, for about ten years, the Mattru Hospital was run by a team of dedicated nurses.

Construction on the hospital began in 1949, and nurse Oneta Sewell opened a dispensary at Mattru that year. Throughout the 1950s, the mission tried to recruit a doctor, but in vain. Nevertheless, the work at Mattru Hospital expanded under the leadership of nurses, who also started a nursing school to train Sierra Leoneans.

In 1957, field superintendent Marion Burkett learned about Dr. Alvin French, who worked with another denomination but was being sent home early after just one year on the field. He invited French to complete his term at Mattru Hospital. and French agreed.

In May 1957, Alvin and Barbara French and their two children settled in Mattru. The news spread rapidly: the mission hospital had a doctor! Turns out French was more than a doctor—he was also a preacher, having pastored a church for two years while in medical school. The Methodist pastor’s son began leading the morning devotions for hospital staff, and presented the Gospel to patients through an interpreter.

Dr. French and his family served just two years–two very good years. And that was enough. In 1959, Dr. Sylvester Pratt was ready to take over.

Pratt, a Sierra Leonean, had worked as a nurse during the 1940s at government hospitals in Bonthe, Bo, and Freetown. Wanting to become a medical doctor, he left for the States and, in 1957, graduated from the Indiana University medical school. He interned in Dayton, Ohio, went to England to take a course in tropical medicine, and finally returned to his homeland.

In November 1959, Dr. Pratt went to Freetown for a weekend, supposedly on business. Supposedly. He returned with a new bride—Dorothy, who was then head nurse of a government hospital in Freetown. They were married on November 4 in Dorothy’s church, a Methodist church, with UB missionaries Russ and Nellie Birdsall present. Sylvester and Dorothy served together at Mattru for 14 years, and along the way had four children.

When Pratt arrived, Mattru Hospital was a 15-bed cement block facility without electricity or plumbing. In the years ahead, he expanded it to 34 beds. An 18-bed pediatric unit was added in 1966, a maternity ward in 1970, plus x-ray and laboratory facilities. Whereas Dr. French had done only a few minor surgeries, Pratt set up an operating room and the hospital was soon swamped with patients in need of surgery, many of whom had to be turned away.

Skilled Sierra Leoneans joined the medical team, along with a continuing string of nurses and other medical practitioners from North America. Mission director George Fleming wrote of Dr. Pratt, “He did not tolerate anything inferior, whether it were drugs, techniques, or just lack of facilities. He had a captivating personality, and that caused people to want to do the job and do it right, though it might be quite difficult. He was stern with the patients, but could joke with them and make them laugh.”

Sick babies often arrived with charms around the neck, waist, wrists, and ankles. Before Pratt would treat them, he insisted that the charms be removed. Fleming wrote, “There was one thing he wanted them to get straight—that God was the doctor at the hospital, and he [Pratt] was only God’s instrument.”

Sylvester Pratt returned to the States in 1973 and became senior medical officer for General Motors. He died of cardiac arrest on May 4, 1989, while attending a medical conference in Boston. At the time of his death, his oldest child, Melody, was a physician in Philadelphia, and two more children were enrolled in medical school. Dorothy Pratt passed away in 2008.

Bishop Lloyd Eby (right) passed away on November 27, 1969. He had lived a full life–missionary in Sierra Leone, pastor, planter of many churches, and bishop for eight years (1949-1957).

Bishop Lloyd Eby (right) passed away on November 27, 1969. He had lived a full life–missionary in Sierra Leone, pastor, planter of many churches, and bishop for eight years (1949-1957).

The funeral was held on Saturday morning. It was quite an ecumenical event—a true tribute to William Otterbein, who wasn’t very concerned about denominational labels. Most of Baltimore’s ministers attended. A Lutheran minister, with whom Otterbein had labored for 27 years in Baltimore (and the son of Otterbein’s neighbor at his Tulpehocken pastorate), preached in German. Then a Methodist minister spoke in English. An Episcopal minister led the graveside ceremony in the church yard. Curiously, no United Brethren ministers participated in the funeral services. Newcomer and Hoffman had engagements in Pennsylvania.

The funeral was held on Saturday morning. It was quite an ecumenical event—a true tribute to William Otterbein, who wasn’t very concerned about denominational labels. Most of Baltimore’s ministers attended. A Lutheran minister, with whom Otterbein had labored for 27 years in Baltimore (and the son of Otterbein’s neighbor at his Tulpehocken pastorate), preached in German. Then a Methodist minister spoke in English. An Episcopal minister led the graveside ceremony in the church yard. Curiously, no United Brethren ministers participated in the funeral services. Newcomer and Hoffman had engagements in Pennsylvania.