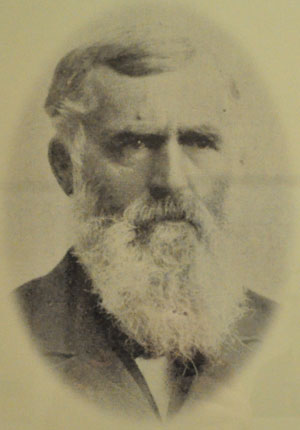

25 May On This Day in UB History: May 25 (Andrew Zeller)

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.

On May 25, 1839, Bishop Andrew Zeller, 84, passed away at his home near Germantown, Ohio. At the time, the Miami Conference, which consisted mostly of churches in Ohio, was holding its annual meeting in Germantown, near Dayton.

It seemed clear that death was approaching. One visitor asked Zeller if he thought his last hour had come.

Zeller replied with a look of pleasure, “I hope so.”

He then crossed his arms and, in the words of UB historian John Lawrence, “calmly fell asleep in Jesus.”

Andrew Zeller was born in eastern Pennsylvania in 1755, and was married in 1779; he and Catherine would have nine children. Catherine died in 1822, but he remarried five years later.

We don’t know much about Zeller. He became a Christian in 1790 and, at some point, entered the ministry. Traveling preachers often stopped at his home; Christian Newcomer’s journal makes a number of references to staying at the Zeller home and holding services there.

Around 1806, Zeller bought several hundred acres for a farm in what was then considered the “far west”–Germantown, Ohio. He started a United Brethren church on his farm–the first UB church west of the Alleghenies.

In 1810, Christian Newcomer came to organize the Miami Conference (named after the Miami Valley of western Ohio). It was only the second United Brethren conference to form. Zeller was listed among the ministers.

When did Zeller become a bishop? Some UB historians say he was elected bishop at the 1815 General Conference, which Zeller attended. Others say it was 1817. It seems strange that General Conference would have left Christian Newcomer to serve as the only bishop until 1817, since we’d always had two bishops. However, at the time of the 1815 General Conference, Zeller wasn’t even an ordained minister. Two weeks after the conference, when the Miami Annual Conference met, Bishop Newcomer ordained a minister named Christian Crum, and then assisted Crum in ordaining seven other ministers–one of whom was Andrew Zeller.

It is also recorded that Zeller was “ordained” as a bishop in 1817. That’s a practice that didn’t last long. Joseph Hoffman was similarly ordained as a bishop in 1821, but we then discontinued the practice. It was decided that when you’re ordained to the ministry, you’re ordained for whatever form that ministry takes–whether as a circuit-riding preacher, superintendent, or bishop. A second ordination was meaningless and unnecessary.

Zeller was considered to be a plain and modest speaker. But it was said of him, “His life was a sermon.” Henry Spaythe, a contemporary of Zeller, wrote of him:

“What a contrast between what men call great preachers and those God approves. One hears the echo of applause; the other is followed by a train of happy souls bound to meet him in heaven.”

On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.

On May 24, 1988, missionary nurse Patti Stone arrived at the Harbour Hospital and Institute for Tropical Medicine in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The UB Mission in Sierra Leone had chartered a specially-equipped medi-vac Lear Jet from Munich, Germany. Patti was comatose. She received the best possible care from specialists, but didn’t respond to any treatment.

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821.

May 22, 1799, seems to have been a disappointing day for Martin Boehm (left) and Christian Newcomer (right). They were holding a two-day meeting at the home of Andrew Zeller, who would go on to become a bishop, serving 1817-1821. The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the

The 1869 General Conference convened on May 20, three weeks after the

On May 14, 1988, John Buddy Labor graduated from Huntington College with a degree in Business. He was from Bumpe, Sierra Leone. His father, John Labor, was principal of Bumpe High school and a longtime leader in Sierra Leone Conference.

On May 14, 1988, John Buddy Labor graduated from Huntington College with a degree in Business. He was from Bumpe, Sierra Leone. His father, John Labor, was principal of Bumpe High school and a longtime leader in Sierra Leone Conference.