05 May On This Day in UB History: May 5 (Bishop Edwards)

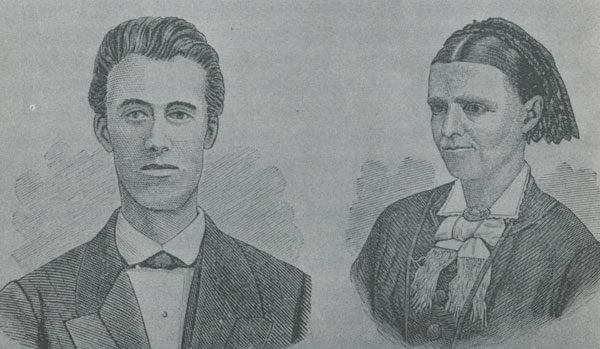

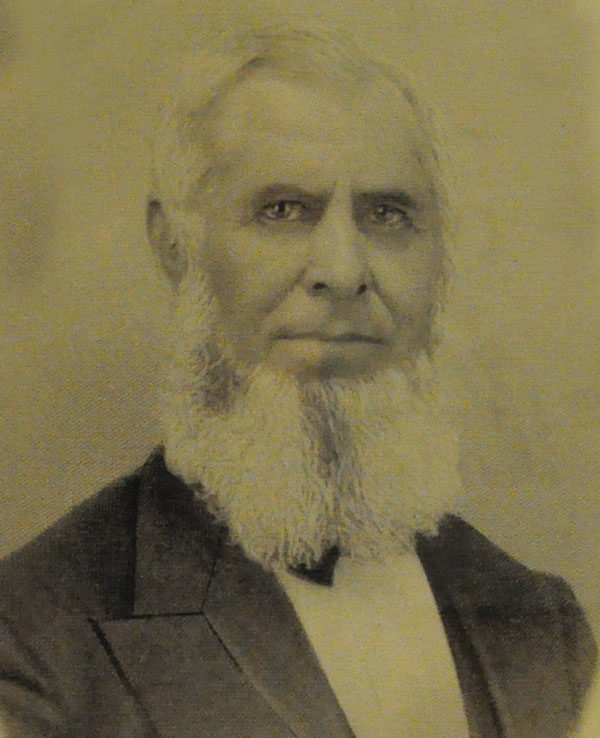

David Edwards, Bishop 1849-1876

On May 5, 1816, David Edwards was born in Wales. He would become one of our longest-serving bishops–27 years, 1849-1876–and one of the most influential. During that time, he played a role in starting our first college, a seminary, our missionary society, and our denominational publication and publishing house. A fellow bishop remarked, “I have looked upon Bishop Edwards on every side. He is the best man this Church has ever yet had. It has never seen his like; it will be years before it finds his equal.”

Edwards’ family came to America when he was five years old, lived two years in Baltimore, and in 1823 moved into Ohio. He was converted at age 18 in a United Brethren meeting, and a year later, in 1835, he was licensed to preach. They didn’t dilly dally back then.

Edwards was assigned to the Brush Creek circuit, which included 28 appointments spread over five counties; he traveled 360 miles making one round. For the next several years, he was assigned to a different circuit each year. In 1839 he married Lucretia Hibbard, whose father was both a lawyer and a United Brethren minister; her brother was also a UB minister, and a sister married a UB minister.

Like many ministers back then, Edwards had very little formal education but was an avid self-learner, constantly reading on horseback and wherever he found to stop for the night. He began to be noticed as a young preacher of tremendous potential, described as studious, a powerful preacher, prudent, methodical, and fearless.

The 1845 General Conference elected him as editor of The Religious Telescope, the denominational publication. During the next four years, he put the Telescope on solid financial footing, and took it from semi-monthly to weekly. As editor, he strongly defended the church’s stands against slavery, alcohol, and Freemasonry.

Edwards was also a zealous advocate of entire sanctification; holiness of heart and life became a central theme throughout the rest of his ministry. Wrote biographer Henry Adams Thompson doubted that anyone else could explain entire sanctification “more clearly, more profoundly, and in a way less liable to objection.” He said many other “best minds in the church” embraced the doctrine.

Historian John Lawrence said Edwards tended to come across as “unnecessarily rigid” because of his stern adherence to his convictions, and that the “set of his teeth” seemed to say, “You can neither coax nor drive me from what I believe to be right.”

In 1849, at age 33, Edwards was elected bishop, and continued in that role until age 60. During his last term, he suffered much from illness–cancer, probably, which advanced quickly and painfully. He died June 6, 1876, with one year left in his seventh term.

Thompson wrote, “However much good men may have differed with him in their views, none doubted the purity of his motives or the uprightness of his character. As a preacher he had few, if any, superiors in the church….He knew how to live and walk by faith….He would not only urge the ministry to try to do more and better work for the Master, but he led them by precept and example in the doing of it.”