22 Dec UB Offices Closed Next Week

The United Brethren National Office will be closed December 23 – January 1. The office will reopen on January 2.

(260) 356-2312

The United Brethren National Office will be closed December 23 – January 1. The office will reopen on January 2.

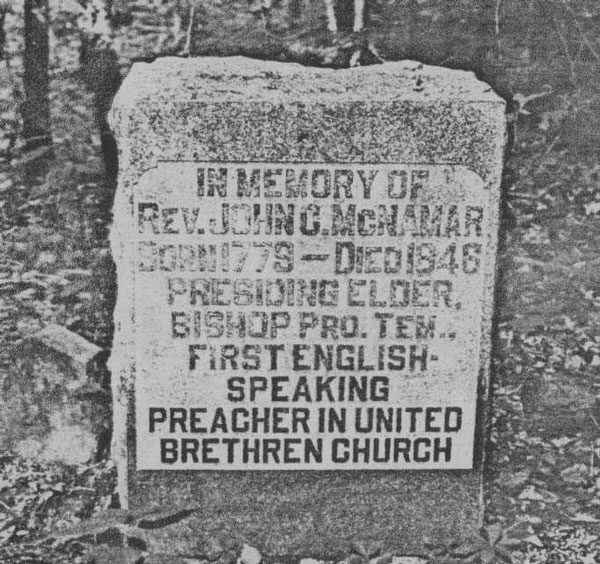

The gravestone of Rev. John McNamar, the first English-speaking UB preacher.

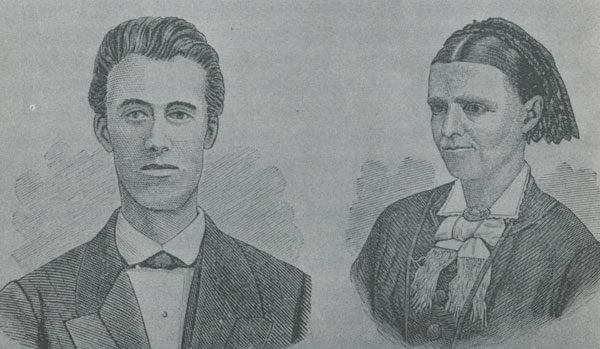

John McNamar was married December 19, 1805, in Xenia, Ohio. We can assume they said their vows in English, because McNamar is heralded as the first English-speaking United Brethren minister. Says so on his gravestone. All of the founders and early ministers spoke German. But in the early 1800s, most of the church’s westward expansion occurred among English-speaking people, and McNamar was in the forefront.

McNamar was born in Virginia in 1779, of Scottish-Irish descent. It’s not know when exactly he moved to Ohio. However, in 1811 he became a schoolteacher in Germantown, Ohio, where future bishop Andrew Zeller lived. He became a Christian during an evangelistic meeting in Zeller’s barn, and Zeller shepherded im toward the ministry. In 1814 he became a minister in Miami Conference (the Miami Valley of southwestern Ohio) and was ordained in 1816.

John McNamar

John Lawrence wrote, “He devoted himself to the Master’s work with a singleness of aim, and resoluteness of purpose, which have seldom been equaled. He planted the larger part of the early English United Brethren churches in southwestern Ohio and southern Indiana.” He was also successful in recruiting new ministers. By 1820, another eight English-speaking ministers had joined Miami Conference and were doing their own part in spreading the Gospel.

McNamar is described as brave, unpretentious, practical. He spoke slowly and distinctly, and used a lot of humor. He zealously expounded on and defended the fundamental Christian doctrines, like the divinity of Christ, which he often preached to “immense congregations at camp-meetings.” He was a strong theologian and could wax eloquent. But, “His object was to save men; and he had the happy faculty of following up a clear exposition and masterly defense of some great truth with a heart-searching application.”

William Weekley wrote, “Mr. McNamar had the evangelistic spirit to an intense degree, and the spread of the Redeemer’s kingdom was to him paramount to all things else. He had the zeal of the early disciples, and, regardless of the cost to himself, went everywhere in his large frontier parish preaching the gospel of the kingdom. He was a man of superb courage. To him even roads and paths seemed useless. If his horse could not carry him, he led the horse, or, leaving him behind, went on foot. He frequently slept in the wilderness, but he was never lost. His long journeys were often made extremely difficult by untoward condition of the roads and by overflowing creeks and rivers.”

Despite having to travel long distances over rough terrain, he was known for punctuality. Fellow minister George Bonebrake testified, “When the time arrived for him to start to an appointment, he was off. He would wait for no one, and listened to no excuses. Rain, snow, mud, swollen streams, and floating causeways–any of these, of all of them combined, could not change his purpose. Nothing but a physical impossibility would detain him from an appointment.”

Weekley said multitudes of people flocked to hear McNamar preach. “He was unsurpassed in his qualities to capture new communities. There must have been peculiar power in his preaching and a peculiar adaptability to the hearts and to the spiritual needs of the people.”

By all accounts, McNamar was a gifted, natural leader. He became highly respect in the denomination and helped shape important legislation. He was elected bishop in 1833 to succeed Christian Newcomer (who had died during his final term in office), but he declined for unknown reasons. However, he seemed to prefer working in the trenches. Henry Spayth wrote, “J.C. McNamar, a true son of the gospel, determined to march in the front ranks of the ministerial army. He chose the frontier country for his field of gospel labor. To forego all sorts of comfort, to range the forest, to carry the gospel to the newly-arrived inhabitants, to seek the lost and scattered of Israel, was his employment, no matter how poor or destitute they or himself were.”

McNamar toiled faithfully for over 30 years. He passed away in 1846.

The National Office staff gather around Jane and Rod Seely as Bishop Todd Fetters (left) prays for them.

Jane Seely has concluded eight years of work at the United Brethren National Office. She came to the office in January 2009 as the part-time shipping clerk, and in May 2011 was named fulltime manager of Church Resources, our curriculum marketing and distribution operation.

With the decision this fall to discontinue the marketing operation, Jane’s position was no longer needed. Jane saw it coming, and accepted the decision with the utmost graciousness.

With the decision this fall to discontinue the marketing operation, Jane’s position was no longer needed. Jane saw it coming, and accepted the decision with the utmost graciousness.

Jane grew up in the College Park UB church in Huntington, Ind. Jane and her husband, Rodney, now attend First Nazarene Church. Rodney is a sales rep for a building materials wholesaler.

Jane graduated from beautician’s college in 1977, and worked as a cosmetologist in Huntington until joining the National Office staff fulltime in 2011. In addition, she makes jewelry, which she frequently displays and sells at fairs, craft festivals, and other events.

The National Office held a farewell luncheon for Jane at the beginning of December. A few days later, she started online classes to become a Health Coach/Life Coach, and is very excited about this new chapter in her life.

We appreciate Jane’s years of service to the churches of our denomination, and the cheerful spirit she brought to the office. She will be missed.

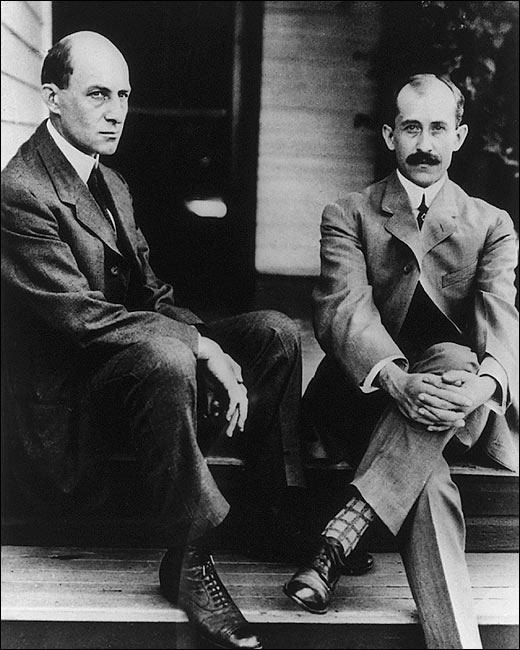

Wilbur (left) and Orville Wright

At the time, their father, Milton Wright, was in his 18th year as a United Brethren bishop. He would retire two years later, in 1905. He had spearheaded the departure of the “radicals”–our group–from the main body of the United Brethren denomination, and led us in starting over. Apart from that, we would all be United Methodists, and there would be no Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

There are stories of Orville and Wilbur teaching Sunday school, but they weren’t generally church-going guys. They helped their father in his lawsuits and other controversies, but otherwise didn’t get much involved in the church.

In 1910, Orville asked his father, then 81, if he wanted to take a ride in an airplane. Milton did. The flight lasted just under seven minutes. Orville, afraid of how his elderly father would react at being so high above the ground, levelled off at 350 feet. He needn’t have been concerned. Milton leaned close to Orville’s ear and shouted above the roar of the engine, “Higher, Orville, higher!” That’s the story, anyway.

Wilbur Wright died in 1912 after contracting typhoid fever, Milton died in 1917, and the only daughter, Katherine, died in 1929 of pneumonia. Milton’s wife had died in 1889. However, Orville lived until 1948.

In 1944, future bishop Clyde Meadows and Elmer Becker, then in his third year as president of Huntington College, traveled to Dayton, Ohio, to visit Orville, who was then 73. Orville lived in the family home with his housekeeper. They were gracious hosts, and the housekeeper prepared a lovely meal.

Meadows had been sent to talk about the Milton Wright Memorial Home in Chambersburg, Pa., which was named in honor of Orville’s father. They talked about the home for an hour. Then, Meadows recalled in his autobiography, In the Service of the King, they spent nearly four hours talking about airplanes. Orville told about his early days of flying, how he and Wilbur started with gliders and eventually built their own planes, and how they kept experimenting and inventing new parts.

At the time, German cities were being devastated in Allied bombing raids, which killed tens of thousands of people–Hamburg, Dresden, Essen, Cologne. Meadows asked Orville how he felt about his invention being used to cause so much destruction.

Orville replied, “I’ve thought about this a lot. The airplane was due. If Wilbur and I hadn’t developed it, someone else would have. But that is poor consolation. I take comfort in knowing that Wilbur and I gave the airplane to the world in good faith. You can’t withhold a good gift just because someone might misuse it. In that case, God would have to withhold life itself.”

Meadows wrote, “Orville Wright, I realized, was not just an inventor and aviator. He was also a philosopher. It was an inspiration to talk with him.”

John Ruebush

John Ruebush, who pioneered United Brethren ministry in Tennessee, died on December 16, 1881. Since Tennessee was a slave state, and the United Brethren church was vehemently anti-slavery, Ruebush received his share of threats. But he toiled on. William Weekley said he lived with “a complete abandonment of himself to the work and purpose of his life.”

Ruebush was born in Virginia in 1816; his parents were of German descent. He was converted at age 18 and joined the United Brethren church. At age 25, he became a minister in Virginia Conference, and for the next 14 years served churches in Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Weekley described Ruebush as a born leader, fearless, of “aggressive will,” rugged, and with a “startling mental energy.” He was a strong preacher, a successful evangelist, a “master in illustrating great truths,” and “a man of large horizon and of bold enterprises.”

In 1856, Virginia Conference appointed Ruebush to spearhead opening a mission in eastern Tennessee. On April 6, 1856, John, his wife, and their young son headed to Tennessee in a buggy, a journey which took two weeks. He began looking for UB members who had relocated from Virginia, and found 13 of them scattered over a large area. He began preaching, and within a year had formed and 11-point circuit. He preached wherever he could–in schools, a Methodist church, private homes, or in the woods.

In December 1856 he wrote, “I never felt as well satisfied that I was where God wanted me to work as I have since I am on this mission. My congregations are large and very attentive. I have more calls than three men can fill. We feel the need of church houses of our own. I have been preaching in some of the schoolhouses belonging to the county, but they will not accommodate the people. When it is not too cold, I preach out of doors.”

In one community, a man bitterly opposed to Christianity took up the floor of the schoolhouse where Ruebush planned to preach. Undeterred, Ruebush preached from the doorstep, and when he finished, at least a dozen people were kneeling in prayer…including the man’s wife. The antagonist came to him later that day. He tearfully apologized, asked for forgiveness, and invited Ruebush to hold services in his own home. Weekley says, “A great revival followed, and the first United Brethren church in the state was subsequently built in this community.”

The believers began praying for a local family that ran a distillery. Within a week, every member of that family had been converted, and the still was torn down. One family member became a United Brethren minister for over 20 years.

With the onset of the Civil War, things got dangerous for Ruebush and family. He scaled back his work to just the community where he lived, but that wasn’t enough. He finally took his family out of the state. He would later write: “These were months in which there were many trying experiences, narrow escapes, privations, fatigues, exposure, and financial losses.”

When the war ended, Ruebush returned. Tennessee Conference was organized in 1866 with 209 members and three ministers.

In 1869, Ruebush transferred back to Virginia Conference for the rest of his ministerial career. In the fall of 1881, at age 65, he baptized some people by immersion and then rode three miles home in his wet clothes. He contracted pneumonia and died on December 16, 1881.

During the early 1990s, the escalating rebel war in Sierra Leone dominated every meeting of the Missions Commission. On May 16, 1994, at the end of an emergency two-day meeting, the Commission made a painful decision: “Be it resolved that we mandate that all missionaries close out their respective ministries with promptness and with judicious turn-over, and depart Sierra Leone no later than December 31, 1994.”

The Missions Commission cited many reasons behind the decision: the dangerous rebel activity, the political instability, the difficulty in recruiting and sending new missionaries. The nationalization process begun in the mid-1980s decreased the need for missionaries. It was clear that the Sierra Leone churches could function effectively without missionary involvement.

Besides, the resolution said, “We went to Sierra Leone in the 1800s to evangelize the people. We established 40-some churches, and they now carried responsibility for evangelism. None of the present missionaries were sent specifically to evangelize.”

Mission Director Kyle McQuillen assured people that we would continue our financial commitment of approximately $120,000 to the national church and its ministries. “We are in no way abandoning our brethren in Sierra Leone,” he wrote. But, he said, “This is not a temporary move. It is a final withdrawal of missionary personnel.”

Brian and Gail Welch (a teacher and nurse in Mattru) and family left in May 1994, along with nurse Neita Dey. The Tom and Kim Datema family, who worked in community development, returned to Indiana in August. Hospital Administrator Tom Hastie left on October 1, rejoining his wife and children, who had returned to Detroit in June. That left just Sara Banter and Nadine Hoekman, nurses at Mattru, and Phil and Carol Fiedler in Freetown; Phil taught at Sierra Leone Bible College and served as Director of Missionary Affairs.

On December 13, 1994, the Fiedlers and Sara Banter left Sierra Leone, flying out of the country with Bishop Ray Seilhamer and Kyle McQuillen, who had arrived ten days before to attend Sierra Leone Annual Conference. Nadine Hoekman chose to remain in Sierra Leone as an independent missionary. She signed documents releasing responsibility for her welfare.

Suddenly, for the first time since 1871, there were no United Brethren missionaries in Sierra Leone.

On January 1, 1995, rebels attacked Bumpe, where our conference headquarters was located, and burned over 75 homes and buildings. In mid-January, Mattru Hospital essentially closed down. Nadine Hoekman paid all the workers, then locked things up. On January 30, rebels captured Mattru and, during the next eight months, used our hospital as a training base.

On December 10, 1985, an historic annual conference began in Sierra Leone. Since the 1850s, when UBs first entered Sierra Leone, missionaries had been in charge of our work. Jerry Datema felt that needed to change, so when he became bishop in 1981, he appointed a group to plan for nationalization. That plan was implemented at the December 1985 conference.

Bishop Datema chaired the 1985 Sierra Leone Annual Conference, but as he later wrote, “National leaders really ran the show, rather than missionaries as in previous years.”

Rev. Henry Allie, a blind pastor, was elected to a three-year term as the first General Superintendent, the highest United Brethren leader in Sierra Leone. Joe Abu and Edward Morlai were chosen as officers to work at the national headquarters with Rev. Allie. A major shift toward youth occurred that year, as five senior pastors, including former superintendents, retired. Four younger conference superintendents took their place.

Figures from 1985 showed 4,553 members in Sierra Leone. United Brethren schools were reaching over 7000 students in 44 primary schools, and over 1000 students attended our four high schools. The hospital was going full steam.

Bishop Datema wrote in April 1986, “During annual conference, I thought, I don’t think any of us fully realize how much we have going for us in Sierra Leone.”

We had capable missionaries working hand-in-hand with the national church. Good camaraderie existed between nationals and missionaries, with mutual trust and openness. We had highly respected national leaders, many growing churches, an optimistic spirit, and much confidence.

Datema continued, “The Sierra Leoneans deeply desire to see the church grow. It is their church, and the fact that they have assumed responsibility has made a great difference.”

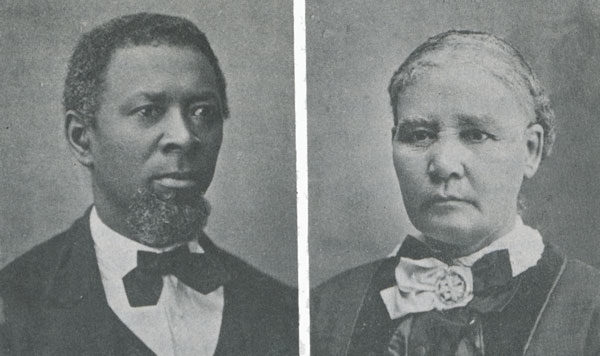

Oliver and Mahala Hadley, missionaries to Sierra Leone, 1866-1869

Joseph and Mary Gomer

Oliver and Mahala Hadley were among the first United Brethren missionaries in Sierra Leone, serving alone from December 1866 to March 1869.

Those two years were not kind to Mahala. She left her 14-month-old daughter with a grandparent, knowing she wouldn’t see her for up to three years. In Africa, she gave birth to a daughter who lived just six weeks; late one night, she and Oliver watched helplessly as the infant struggled and died. She saw her husband gradually break down from a variety of ailments. They returned to America at the end of March 1869. A few days later, Oliver died at age 31. And ten days after that, her infant son died.

But Mahala Hadley was not done with Sierra Leone.

The 1869 General Conference almost discontinued the work in Sierra Leone. No missionaries served there for nearly two years after the Hadleys left. Then the Mission board appointed Joseph and Mary Gomer, an African-American couple. They arrived in Sierra Leone in January 1871 and the work immediately took off.

On December 9, 1871, Mahala Hadley arrived in Shenge, the Sierra Leonean village which she, Oliver, and their infant son had left just two years before. During the next three years, she saw the fruit which she and Oliver had only dreamed of.

Mrs Hadley reported that Gomer had built a nice tomb over her daughter’s grave. She wrote on December 19:

“I am truly thankful to God for permitting me to see with my own eyes the wonderful change which he has wrought among this people since my return to America. And I think no one can gainsay what has been wrought by our devoted missionaries, Brother and Sister Gomer. They have been pushing the battle to the enemy’s gates….

“The people who visit Shenge will see it no longer the place for devil worship, but the place for the worship of God. Already, the word of this good work is spreading through the towns and country, and the change is observed in the people here by prominent persons in Freetown. Brother Gomer has scattered much religious truth, and much of the seed is taking root in good ground—that is, in honest seeking hearts.”

Gomer wrote of Mahala: “Mrs. Hadley is an excellent worker. She will do much good here; but she is working too hard; she will make herself sick.” He said he planned to visit some villages, and said, “Mrs. Hadley wishes to go out also, and tell the people about Jesus.”

Mahala Hadley worked alongside the Gomers for three years. It was a good relationship, and they saw continued fruit from their labors.

Dr. George Fleming wrote, “What kind of a spirit could possibly prompt this sister to return to the foreign field where sorrow and death had seemed to stalk her very life? The answer is not difficult to find—the Holy Spirit! During her second term, she was favored by the mercies of her Heavenly Father to taste the sweetness of victory after experiencing round after round of disappointment and tears.”

Thirty congregations of the United Brethren in Christ gathered November 5-6, 2017, at Rhodes Grove Camp, their traditional meeting place since they founded the camp in 1898. Gathering there for the second annual “UB Connected” event, they far exceeded the goal for a joint missions project. Challenged to raise $11,150 to complete construction of a new UB primary school in Pujehun, Sierra Leone, West Africa, eleven participating congregations raised $27,656. An additional $3,750 was contributed during the gathering by individuals, making the total raised $31,406, almost triple the goal.

Jeff Bleijerveld, Executive Director of UB Global, presented a challenge on Sunday afternoon, followed by an address by Rev. John Pessima, Bishop of Sierra Leone National Conference.

Following a fellowship supper, the United Brethren Association for Church Development held a brief business meeting during which two new members were elected to the Board. Officers for 2018 are as follows: Rev. Michael Allen Mudge, President; Mr. Glen Gochenauer, Vice-President; Rev. David Rawley, Secretary; and Mr. Marvin Shubert, Treasurer. Members-at-Large are Rev. John Christophel and Mrs. Fonda Cassidy. Representing the UB National Office in Huntington, Ind., is Rev. Greg Helman, and representing the Rhodes Grove Camp Board is Rev. Keith Elliott. Completing the Board are Rev. Keith Sider, representing the Sider Insurance Agency, and Ms. Angela Monn as Executive Director.

The main event of the gathering was the Sunday evening preaching service featuring US Bishop Todd Fetters. Worship music was offered by the praise team from Prince Street UB Church in Shippensburg. Dr. Sherry Goertz, representing the Rhodes Grove Camp board and Blue Rock UB Church, offered music on the harp during the Communion service. The evening concluded with a reception sponsored by the Sider Insurance Agency.

The Monday morning segment continued the theme of “Unity,” with Dr. Ray Seilhamer preaching the Scriptures and Joe Abu exhorting. Dr. Seilhamer, retired bishop, currently serves as pastor of the Mount Pleasant UB Church, Chambersburg; and Rev. Abu, a native of Sierra Leone, is pastor of Mount Zion United African Church (UB) in Philadelphia. Leading worship Monday morning was Rev. Derek Thrush, pastor of Devonshire Memorial UB Church in Harrisburg, assisted by Christopher Little V.

This “UB Connected” event brought to a close a year celebrating several milestones for the United Brethren in Christ. The 250th Anniversary of their beginnings took them back to Lancaster, Pa., in July for their every-other-year National Conference, where about 600 attendees took buses to Isaac Long’s Barn to see where their founding bishops first met during a “Great Meeting” in 1767. Rhodes Grove Camp celebrated the 100th Anniversary this year of the purchase of the land by the UB Pennsylvania Conference in 1917 with the conclusion in June of a capital campaign that raised almost $400,000, more than any previous fundraising campaign.

The camp also marked its 75th Anniversary of the first Summer Youth Camp in 1942 with an enrollment this year of 531 campers in ten camps over six weeks, their highest enrollment since 2004. This year also saw the launch of a new ministry with a satelite camp being held with Devonshire Memorial UB Church in Harrisburg. The 50th Session of Family Camp was also marked over Memorial Day Weekend with an all-time record attendance of 331 registrants with well over 400 for the Sunday evening service.

In celebration of all these milestones, plus the 500th Anniversary of the beginning of the Protestant Reformation on October 31, 1517, UB pastor Michael Mudge of Cumberland, Md., published a history book, with chapters covering the Protestant Reformation, the United Brethren in Christ, the Capt. Lee Rhodes family, campmeetings, the Pennsylvania Conference, Milton Wright Home, summer youth camps, etc. Entitled Tabernacle Faith: A History of Rhodes Grove Camp, the book is 119 pages long with 195 photographs and is thoroughly indexed. Of two hundred copies printed in May, only about twenty copies remain to be sold. They are available at the main desk in the lobby of the Meadows Conference Center at Rhodes Grove Camp.

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?”

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?”

At the time, Meadows chaired the draft board in Chambersburg, Pa., where he pastored the King Street United Brethren church (it would be another 20 years before he was elected bishop). Up to that point, it was a fairly simple job, with only a few people being inducted each month. But with America’s entrance into the war, they began drafting dozens of men at the same time.

Meadows went to Judge Watson Davidson, who served on the committed that selected the three members of the draft board. He argued, “I don’t think it’s right for me to pastor a church and chair the draft board in the same community. I’d like to resign as chairman and enter the military as a chaplain. I’m qualified for that.”

Judge Davidson refused his request. “There are some things from which you can’t resign. Being a father is one of them. Another is your patriotic duty.”

Meadows chaired the draft board 1940-1946; the other two members were World War I veterans. The Chambersburg community sent over 2500 young men into World War II. Many, of course, either died or returned with terrible wounds. Meadows could not escape recognizing his role in the lives of these men.

King Street’s Christian Endeavor society corresponded monthly with 219 soldiers who had some connection with the church—ten of whom died serving their country. They sent materials telling how the local athletic teams were doing, who had gotten married, who was on furlough, local news, and information about the church.

One member of the King Street choir was serving with the Army in Italy. The soldier wrote, “I saw the dates when you were holding communion. I was out on the firing line at the time, but with some water from my canteen and a little morsel of Army bread, I took communion the same time you did back in Chambersburg.”

One night, as they prepared to send their monthly newsletter to the troops, Betty entered the room. They already knew about the death of Betty’s husband, who had been president of the senior high Christian Endeavor group. Betty had just received his personal effects. They included a pocket-size book of selected Scripture which they had sent him–now bloodstained, because he was carrying it when he was killed. Betty also showed one of the letters, also bloodstained, which the church had sent. The paper was tearing, because he had unfolded and read the letter so many times.

Meadows wrote in his autobiography, In the Service of the King, “You couldn’t have stopped us from sending that letter that night. We knew how much those letters meant.”