17 Dec On This Day in UB History: December 17 (Kitty Hawk)

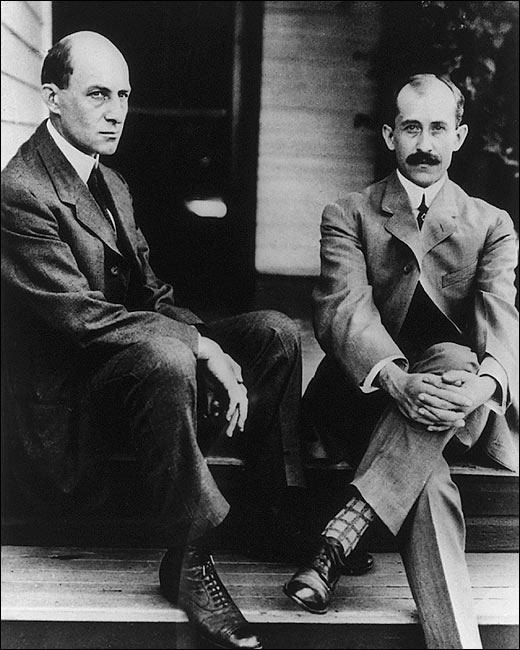

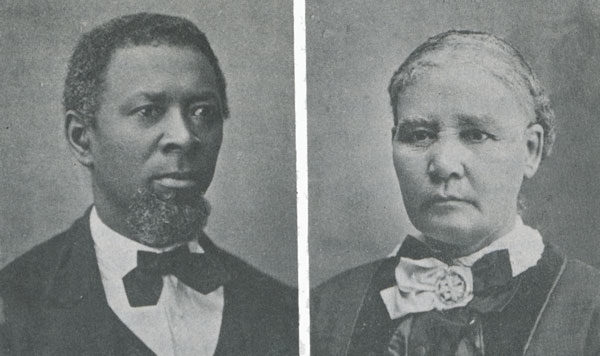

Wilbur (left) and Orville Wright

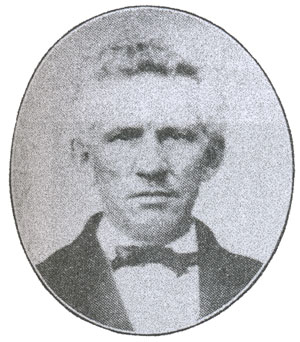

At the time, their father, Milton Wright, was in his 18th year as a United Brethren bishop. He would retire two years later, in 1905. He had spearheaded the departure of the “radicals”–our group–from the main body of the United Brethren denomination, and led us in starting over. Apart from that, we would all be United Methodists, and there would be no Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

There are stories of Orville and Wilbur teaching Sunday school, but they weren’t generally church-going guys. They helped their father in his lawsuits and other controversies, but otherwise didn’t get much involved in the church.

In 1910, Orville asked his father, then 81, if he wanted to take a ride in an airplane. Milton did. The flight lasted just under seven minutes. Orville, afraid of how his elderly father would react at being so high above the ground, levelled off at 350 feet. He needn’t have been concerned. Milton leaned close to Orville’s ear and shouted above the roar of the engine, “Higher, Orville, higher!” That’s the story, anyway.

Wilbur Wright died in 1912 after contracting typhoid fever, Milton died in 1917, and the only daughter, Katherine, died in 1929 of pneumonia. Milton’s wife had died in 1889. However, Orville lived until 1948.

In 1944, future bishop Clyde Meadows and Elmer Becker, then in his third year as president of Huntington College, traveled to Dayton, Ohio, to visit Orville, who was then 73. Orville lived in the family home with his housekeeper. They were gracious hosts, and the housekeeper prepared a lovely meal.

Meadows had been sent to talk about the Milton Wright Memorial Home in Chambersburg, Pa., which was named in honor of Orville’s father. They talked about the home for an hour. Then, Meadows recalled in his autobiography, In the Service of the King, they spent nearly four hours talking about airplanes. Orville told about his early days of flying, how he and Wilbur started with gliders and eventually built their own planes, and how they kept experimenting and inventing new parts.

At the time, German cities were being devastated in Allied bombing raids, which killed tens of thousands of people–Hamburg, Dresden, Essen, Cologne. Meadows asked Orville how he felt about his invention being used to cause so much destruction.

Orville replied, “I’ve thought about this a lot. The airplane was due. If Wilbur and I hadn’t developed it, someone else would have. But that is poor consolation. I take comfort in knowing that Wilbur and I gave the airplane to the world in good faith. You can’t withhold a good gift just because someone might misuse it. In that case, God would have to withhold life itself.”

Meadows wrote, “Orville Wright, I realized, was not just an inventor and aviator. He was also a philosopher. It was an inspiration to talk with him.”

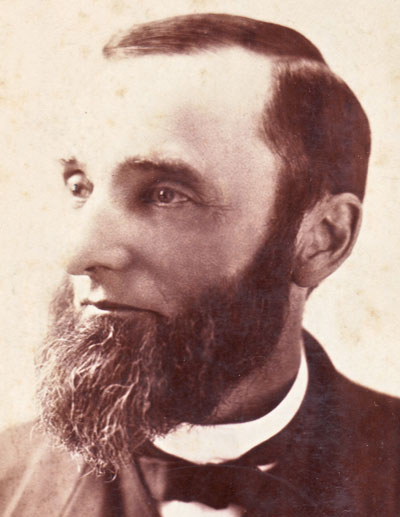

Bishop William Dillon (right) died of pneumonia on December 15, 1919. He served just one term as bishop, 1893-1897. Most of his career was spent in the pastorate and as editor of The Christian Conservator paper.

Bishop William Dillon (right) died of pneumonia on December 15, 1919. He served just one term as bishop, 1893-1897. Most of his career was spent in the pastorate and as editor of The Christian Conservator paper.

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?”

In December 1941, Clyde W. Meadows (right) held revival services at the Trenton Hills UB church in Adrian, Mich. On the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, he and Rev. H. B. Peter went visiting in the Adrian community. As they drove down a country road, they were flagged down by another card. The driver scrambled out and said, “Did you know the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor this morning?” During her furlough in 1983, Shirley Fretz (right) had a difficult decision to make. Her father had been hospitalized with cancer almost continuously since July 1982. Should she stay home and await his death, or return to Sierra Leone in December as scheduled?

During her furlough in 1983, Shirley Fretz (right) had a difficult decision to make. Her father had been hospitalized with cancer almost continuously since July 1982. Should she stay home and await his death, or return to Sierra Leone in December as scheduled?