17 Nov On This Day in UB History: November 17 (William Otterbein)

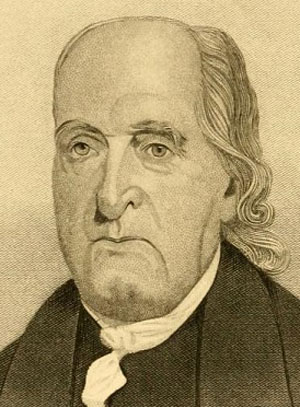

Philip William Otterbein. This painting was done in 1810, three years before Otterbein’s death.

William Otterbein, one of the founders of the United Brethren Church, died on November 17, 1813. He was 87 years old. He had been a minister for 65 years, and a bishop for 13 years. Martin Boehm, the other founder and bishop, had died a year-and-a-half before.

Since June, Otterbein’s health had been failing. He continued as pastor of what is now called Old Otterbein Church in Baltimore, and for the most part continued his ministerial responsibilities. But, as A. W. Drury wrote in his biography of Otterbein, “His fund of vitality was gone.”

By the time October arrived, Otterbein had stopped preaching. Rev. Frederick Schaffer, who had emerged from Otterbein’s ministry at his first pastorate, in Lancaster, Pa., filled the pulpit. Meanwhile, everyone around knew of Otterbein’s deterioration.

At the time, Otterbein was the only ordained United Brethren minister. UB ministers Christian Newcomer and James Hoffman came to Baltimore at the beginning of October with the request that Otterbein ordain them, so they could then ordain others in an unbroken chain from Otterbein to…well, to the present. That happened on Saturday, October 2, during a ceremony in Otterbein’s home. He also used the occasion to ordain Frederick Schaffer. The next day, both Newcomer and Hoffman preached at Old Otterbein Church, and Schaffer joined them in administering communion to the congregation. Newcomer and Hoffman left town the next day.

For the next six weeks, Otterbein’s health continued to decline. He finally passed away at 10:00 pm on Wednesday, November 17. His final words were recorded as, “The conflict is over and past. I begin to feel an unspeakable fullness of love and peace divine. Lay my head upon my pillow and be still.”

The funeral was held on Saturday morning. It was quite an ecumenical event—a true tribute to William Otterbein, who wasn’t very concerned about denominational labels. Most of Baltimore’s ministers attended. A Lutheran minister, with whom Otterbein had labored for 27 years in Baltimore (and the son of Otterbein’s neighbor at his Tulpehocken pastorate), preached in German. Then a Methodist minister spoke in English. An Episcopal minister led the graveside ceremony in the church yard. Curiously, no United Brethren ministers participated in the funeral services. Newcomer and Hoffman had engagements in Pennsylvania.

The funeral was held on Saturday morning. It was quite an ecumenical event—a true tribute to William Otterbein, who wasn’t very concerned about denominational labels. Most of Baltimore’s ministers attended. A Lutheran minister, with whom Otterbein had labored for 27 years in Baltimore (and the son of Otterbein’s neighbor at his Tulpehocken pastorate), preached in German. Then a Methodist minister spoke in English. An Episcopal minister led the graveside ceremony in the church yard. Curiously, no United Brethren ministers participated in the funeral services. Newcomer and Hoffman had engagements in Pennsylvania.

Otterbein didn’t have many possessions to pass on. He willed $50 to Miss Elizabeth Drucks, a woman “now living in my family…as a testimony of my esteem for her.” Everything else he willed to “my friend Elizabeth Schwope, as a small but the only compensation in my power for her faithful services and uncommon attention to me for many years past.”

His most important legacy, as Drury points out, was the nearly 100 ministers who had been raised up under his influence, and who were now preaching the Gospel in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio—the core of a movement which, within 40 years, would spread from coast to coast.

During the last year of his life, Otterbein became concerned about whether or not the United Brethren movement would survive. He summoned two UB ministers, Christian Newcomer and Jacob Baulus, and they talked about the state of the church. They apparently relieved his concerns. Before Newcomer and Baulus left, Otterbein told them,”The Lord has been pleased graciously to satisfy me fully that the work will abide.”

No Comments