March 6, 2018

|

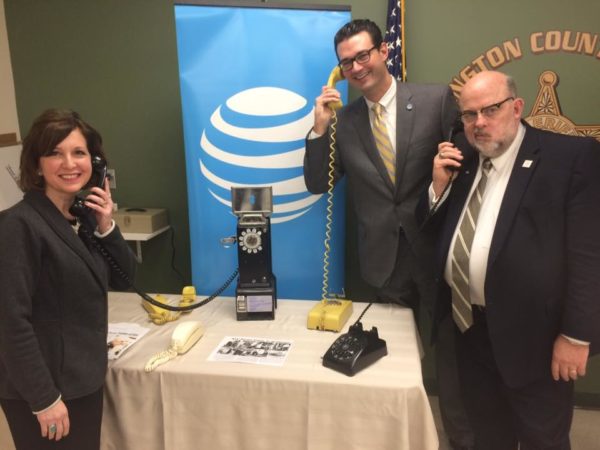

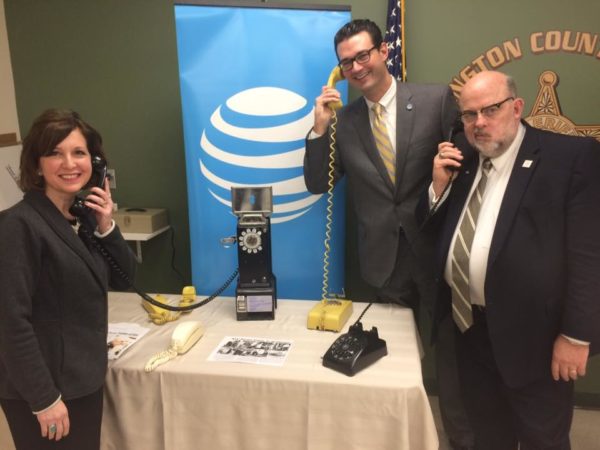

Demonstrating 1968 phone technology are Mayor Brooks Fetters (right) with Indiana state treasurer Kelly Mitchell and AT&T Indiana president William Soards.

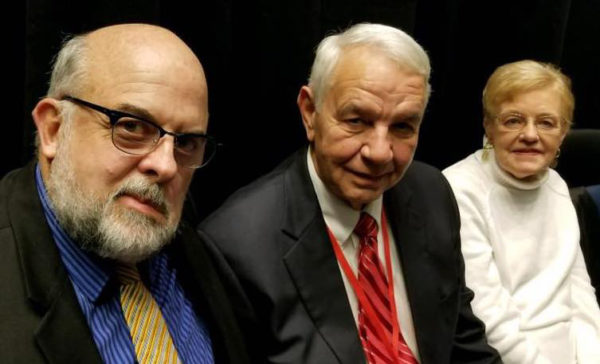

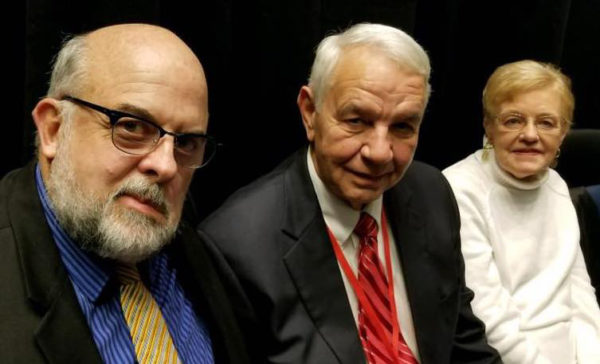

Brooks Fetters (left) with Ken and Kay Sunseri at the commemoration in Washington, DC. Ken is the current mayor of Haleyville, Ala., and Kay’s father was mayor when the first 911 call was placed in 1968.

During February and March, events were held to recognize the 50th anniversary of the Emergency 911 call system. Congressman J. Edward Roush (right), a Huntington University graduate and United Brethren member, led the crusade to implement the system.

During February and March, events were held to recognize the 50th anniversary of the Emergency 911 call system. Congressman J. Edward Roush (right), a Huntington University graduate and United Brethren member, led the crusade to implement the system.

Brooks Fetters, mayor of Huntington (as well as an ordained United Brethren minister), was part of a group from Huntington that traveled to Washington DC for a commemoration of the 911 system. Also participating was a large contingent from Haleyville, Alabama, where the first 911 call was made on February 16, 1968.

Huntington was the first US city for which Bell Telephone (owned by AT&T) instituted 911 service. Congressman Roush placed the first 911 call to a local policeman on March 1, 1968, placing a call to a local police officer. During that first week, 13 calls to 911 were made by Huntington residents. Prior to that, people had to dial “O” for the operator or look up the specific number for the various emergency services (ambulance, fire, police, etc.). Now, thanks to the efforts of Congressman Roush, 240 million emergency calls are placed to 911 every year across the country.

A recognition was held to mark the March 1 anniversary in Huntington. Participating were Indiana State Treasurer Kelly Mitchell and William Soards, president of AT&T Indiana, along with Mayor Brooks Fetters. A US flag which had flown over the US Capitol was presented in honor of Congressman Roush (made possible by Jim Banks, who now represents the Indiana 3rd District in Congress).

Dr. Roush graduated from Huntington University in 1942, and then served as an officer in the US Army in the European theater during World War II. He served six terms as a Democratic Congressman, followed by several years as director of the Environmental Protection Agency. He was an avid supporter of Huntington University, and even served as interim president in 1989 while President Eugene Habecker was on sabbatical. He was also the denominational legal counsel and served the denomination in other capacities. Ed and Polly Roush were longtime members of College Park UB church in Huntington, Ind. He passed away on March 26, 2004. Roush was the subject of this “On This Day in UB History” post.

The first city in North America to use an emergency number was Winnipeg, in Canada. They used the number 999, which had been used in England since 1937. They switched to 911 after the United States proposed using that number. Mexico used the number 066, but in June 2017 the entire country switched to 911.

Mary Ann Goldsmith, 86, wife of UB minister Rev. Wayne Goldsmith, passed away on March 31, 2018. She was a pastor’s wife for 66 years.

Mary Ann Goldsmith, 86, wife of UB minister Rev. Wayne Goldsmith, passed away on March 31, 2018. She was a pastor’s wife for 66 years.

During February and March, events were held to recognize the 50th anniversary of the Emergency 911 call system. Congressman J. Edward Roush (right), a Huntington University graduate and United Brethren member, led the crusade to implement the system.

During February and March, events were held to recognize the 50th anniversary of the Emergency 911 call system. Congressman J. Edward Roush (right), a Huntington University graduate and United Brethren member, led the crusade to implement the system.