19 Sep On This Day in UB History: September 19 (Meadows Behind the Iron Curtain)

Checkpoint Charlie into East Berlin

On September 19, 1963, Bishop Clyde W. Meadows (right) made the first of what would become six trips into East Berlin. He went in his role as president of the World’s Christian Endeavor Union. He was accompanied by Arno Pagel, a Christian Endeavor leader from Frankfurt, and a young seminary student from Hamburg.

About 500 Christian Endeavor societies functioned in East Germany. Because of the communist hostility toward Christianity and toward Americans, the trip was shrouded in secrecy and need-to-know precautions.

About 500 Christian Endeavor societies functioned in East Germany. Because of the communist hostility toward Christianity and toward Americans, the trip was shrouded in secrecy and need-to-know precautions.

Around one corner, a car was waiting. The three visitors squeezed into the small car, along with a man and his daughter and a husky young man who shadowed Meadows for the rest of the day. The car drove about 20 miles outside of East Berlin to a group of buildings, which turned out to be an institution for mentally handicapped children. They were ushered into one building, where about 30 Christian Endeavor people, ages 25-35, were waiting. Some had traveled up to 300 miles to hear Meadows speak.

They asked him to preach. Meadows said, “I want to speak from Philippians 2:5-¬11, to urge you to take courage and assure you that your oppressors will someday have to bow the knee to Jesus Christ.” Nobody in the room had a Bible, but hands shot up throughout the crowd.

Hands shot up all over the room. Arno pointed to one fel¬low, who stood and recited the entire second chapter of Philippians. Meadows then preached a message which, with interpreting, lasted 30 minutes. They then asked questions about the message. Before long, two hours had passed. Then he was asked to preach another message…and then a third message, with discussion in between each one. They shared a simple meal, and didn’t leave until 7:30 that night.

Back in East Berlin, the car stopped in front of a darkened building, and they went inside. The husky young man took his arm as they walked through a dark entryway and down a pitch-black corridor, up some steps, down another corridor, and into a room where 40 young people waited to see the president of the World’s Christian Endeavor Union.

He preached to them. Then they moved on to another dark building, where he found himself preaching to a group of people in a basement. By then it was 11 p.m.

“Dr. Meadows, can you stand one more?” he was asked.

He responded, “I’m so excited, you could cut off my arm and I wouldn’t notice. Let’s go!”

This turned out to be the largest gathering of all. Nearly 100 people, some of whom he remembered from the first meeting. Meadows was told that they wanted to sing for him. He considered that strange, since it was supposed to be a secret meeting, but figured they knew what they were doing.

The director stood up in front, got everyone’s attention, and then raised his arms and brought the people up just like a choir. Then they “sang” all four stanzas of “All Hail the Power of Je¬sus’ Name.” Every mouth was going—but without a sound.

Meadows wrote in his autobiography, “I was almost overcome. These people wanted to sing the praises of the Lord, but had to mouth the words lest they betray themselves.”

After the song, he preached for the sixth time that day. Nobody in any of the meet¬ings had a Bible, yet someone always stood to recite whatever chapter he chose.

Around midnight, they crossed back into West Berlin. Meadows then asked about the husky young man who had closely shadowed him throughout the day. Arno said, “That young man pledged the other Christians behind the Iron Curtain that he would make sure you were taken care of and that if anything went wrong, he would try to get you out of the country—even at the cost of his own life. He pledged his life for yours.”

During subsequent trips, conditions were relaxed. During the final trips, the Christians he visited sang aloud, and during his final trip in 1979, he carried a Bible and his visa granted him permission to preach. In 1990, with the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the Christian Endeavor societies of East and West Germany merged.

Missionary Gary Brooks (right) recalled seeing the carnage the next morning. “Whole barrios in La Ceiba were just gone, swept out to sea. Gone.” One place along the beach, populated by little shacks, was totally wiped away. Cars lay upside down against buildings. Gary found the body of a woman who had fled her home, and died in her overturned car just 50 yards from the church. One man lashed himself to a tree and refused to come down. The storm uprooted the tree and carried it 500 yards away, where the man’s body was recovered, still tethered to the tree.

Missionary Gary Brooks (right) recalled seeing the carnage the next morning. “Whole barrios in La Ceiba were just gone, swept out to sea. Gone.” One place along the beach, populated by little shacks, was totally wiped away. Cars lay upside down against buildings. Gary found the body of a woman who had fled her home, and died in her overturned car just 50 yards from the church. One man lashed himself to a tree and refused to come down. The storm uprooted the tree and carried it 500 yards away, where the man’s body was recovered, still tethered to the tree. Harold Wust (right) passed away on September 17, 2009. Harold’s father immigrated from Germany to Alberta, Canada, around 1930, and Harold was born there. However, the family returned to Leipzig, Germany, in 1939. In 1940, at age 10, Harold became part of the Hitler Youth, though at that age the Nazi ideology meant little to him.

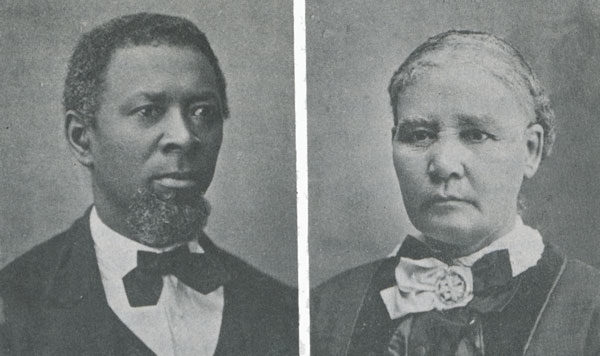

Harold Wust (right) passed away on September 17, 2009. Harold’s father immigrated from Germany to Alberta, Canada, around 1930, and Harold was born there. However, the family returned to Leipzig, Germany, in 1939. In 1940, at age 10, Harold became part of the Hitler Youth, though at that age the Nazi ideology meant little to him. Guillermo Martinez (right) was one of them. Harold and Guillermo often traveled together to villages and churches throughout northern Honduras. Guillermo pastored the large Ebenezer UB church in La Ceiba, but always loved traveling with Harold to visit the country churches.

Guillermo Martinez (right) was one of them. Harold and Guillermo often traveled together to villages and churches throughout northern Honduras. Guillermo pastored the large Ebenezer UB church in La Ceiba, but always loved traveling with Harold to visit the country churches. September 15 has significance for our first two Overseas bishops. Duane Reahm (right), who served as bishop 1969-1981, was born on this date in 1917. His successor, Jerry Datema, passed away on this date in 1994.

September 15 has significance for our first two Overseas bishops. Duane Reahm (right), who served as bishop 1969-1981, was born on this date in 1917. His successor, Jerry Datema, passed away on this date in 1994. In 1981, Jerry Datema (right) concluded 20 years of overseas missionary service–six terms in Sierra Leone, one term in Jamaica. He served the next 12 years as the Overseas Bishop, and chose to retire from that role in 1993. He and Eleanore had planned to move to Jamaica to work with the national church in leadership development. Their missionary barrels were already en route to Jamaica. Then illness crashed in.

In 1981, Jerry Datema (right) concluded 20 years of overseas missionary service–six terms in Sierra Leone, one term in Jamaica. He served the next 12 years as the Overseas Bishop, and chose to retire from that role in 1993. He and Eleanore had planned to move to Jamaica to work with the national church in leadership development. Their missionary barrels were already en route to Jamaica. Then illness crashed in.

On September 5, Rev. Jim Bolich (right) began serving as our denominational Director of Ministerial Licensing. He will continue pastoring the Prince Street church in Shippensburg, Pa., but will carve out 5-10 hours a week for this additional role. This person chairs the Pastoral Ministry Leadership Team, which oversees a range of responsibilities regarding the education, licensing, and stationing of United Brethren ministers.

On September 5, Rev. Jim Bolich (right) began serving as our denominational Director of Ministerial Licensing. He will continue pastoring the Prince Street church in Shippensburg, Pa., but will carve out 5-10 hours a week for this additional role. This person chairs the Pastoral Ministry Leadership Team, which oversees a range of responsibilities regarding the education, licensing, and stationing of United Brethren ministers. Gary’s departure is bittersweet for me. He has been a kind, supportive mentor during these past two years. On the other hand, we will welcome a new team member whom Gary and I both believe will fulfill the role well. Jim Bolich has served at three United Brethren churches in Pennsylvania since 1995—seven years in two associate positions, and since 2002 as senior pastor of Prince Street UB church (Shippensburg, Pa.).

Gary’s departure is bittersweet for me. He has been a kind, supportive mentor during these past two years. On the other hand, we will welcome a new team member whom Gary and I both believe will fulfill the role well. Jim Bolich has served at three United Brethren churches in Pennsylvania since 1995—seven years in two associate positions, and since 2002 as senior pastor of Prince Street UB church (Shippensburg, Pa.).