December 16, 2017

|

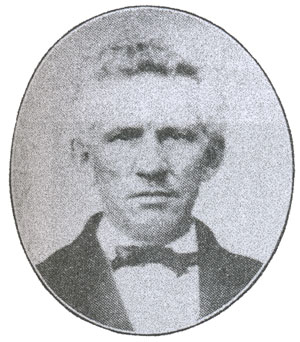

John Ruebush

John Ruebush, who pioneered United Brethren ministry in Tennessee, died on December 16, 1881. Since Tennessee was a slave state, and the United Brethren church was vehemently anti-slavery, Ruebush received his share of threats. But he toiled on. William Weekley said he lived with “a complete abandonment of himself to the work and purpose of his life.”

Ruebush was born in Virginia in 1816; his parents were of German descent. He was converted at age 18 and joined the United Brethren church. At age 25, he became a minister in Virginia Conference, and for the next 14 years served churches in Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Weekley described Ruebush as a born leader, fearless, of “aggressive will,” rugged, and with a “startling mental energy.” He was a strong preacher, a successful evangelist, a “master in illustrating great truths,” and “a man of large horizon and of bold enterprises.”

In 1856, Virginia Conference appointed Ruebush to spearhead opening a mission in eastern Tennessee. On April 6, 1856, John, his wife, and their young son headed to Tennessee in a buggy, a journey which took two weeks. He began looking for UB members who had relocated from Virginia, and found 13 of them scattered over a large area. He began preaching, and within a year had formed and 11-point circuit. He preached wherever he could–in schools, a Methodist church, private homes, or in the woods.

In December 1856 he wrote, “I never felt as well satisfied that I was where God wanted me to work as I have since I am on this mission. My congregations are large and very attentive. I have more calls than three men can fill. We feel the need of church houses of our own. I have been preaching in some of the schoolhouses belonging to the county, but they will not accommodate the people. When it is not too cold, I preach out of doors.”

In one community, a man bitterly opposed to Christianity took up the floor of the schoolhouse where Ruebush planned to preach. Undeterred, Ruebush preached from the doorstep, and when he finished, at least a dozen people were kneeling in prayer…including the man’s wife. The antagonist came to him later that day. He tearfully apologized, asked for forgiveness, and invited Ruebush to hold services in his own home. Weekley says, “A great revival followed, and the first United Brethren church in the state was subsequently built in this community.”

The believers began praying for a local family that ran a distillery. Within a week, every member of that family had been converted, and the still was torn down. One family member became a United Brethren minister for over 20 years.

With the onset of the Civil War, things got dangerous for Ruebush and family. He scaled back his work to just the community where he lived, but that wasn’t enough. He finally took his family out of the state. He would later write: “These were months in which there were many trying experiences, narrow escapes, privations, fatigues, exposure, and financial losses.”

When the war ended, Ruebush returned. Tennessee Conference was organized in 1866 with 209 members and three ministers.

In 1869, Ruebush transferred back to Virginia Conference for the rest of his ministerial career. In the fall of 1881, at age 65, he baptized some people by immersion and then rode three miles home in his wet clothes. He contracted pneumonia and died on December 16, 1881.

The 1833 General Conference provided for establishing a United Brethren publishing house. It took shape in May 1834 in Circleville, Ohio, under the sponsorship of Scioto Conference. William Rinehart, a United Brethren minister in Virginia Conference, had been publishing a paper on his own press called The Mountain Messenger. Scioto asked Rhinehart to move to Circleville to become editor of a United Brethren publication, and they even bought out his little paper.

The 1833 General Conference provided for establishing a United Brethren publishing house. It took shape in May 1834 in Circleville, Ohio, under the sponsorship of Scioto Conference. William Rinehart, a United Brethren minister in Virginia Conference, had been publishing a paper on his own press called The Mountain Messenger. Scioto asked Rhinehart to move to Circleville to become editor of a United Brethren publication, and they even bought out his little paper.