November 2, 2017

|

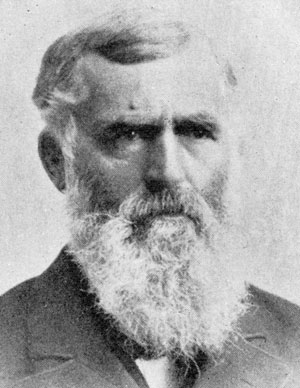

Bishop Daniel Shuck

Daniel Shuck, bishop 1861-1869, died on November 2, 1900. He was 73 years old. During his lengthy service as a United Brethren minister, he served in several states, and deserves considerable credit for rescuing our ministries in California and Sierra Leone.

“He has never made any particular form of church work a specialty,” wrote biographer Henry Adams Thompson. Over the years, in addition to pastoring churches, he helped advance UB ministeres in publishing, higher education, and missions. He became a member of the denominational Missions board when it started in 1853, and was among those who encouraged us to begin work in West Africa.

Shuck’s father, a Kentucky native, was a modest farmer with a firm faith, a man who diligently studied the Bible. He moved his family just across the Ohio River into Corydon County, Indiana. Daniel was born there on January 16, 1827, the fifth of 14 children, seven of them step-siblings (Daniel’s mother, who had been converted by a United Brethren evangelist, died when he was very young). He grew up in a Christian home, in a religious community, with regular visits from several clergy uncles. This kept him on the straight and narrow path, with the early conviction that he would become a minister. He placed his conversion at age 14, when (like Martin Boehm) he was working in a field.

Young Daniel was licensed as a United Brethren minister in 1844, at age 17. His first assignment required a journey of 200 miles to cover the 28 appointments, which he visited every four weeks. In 1845, he planned to enter the State University of Indiana, and even purchased textbooks. However, the bishop and other ministers talked him out of it (back then, Christian folks looked down on college education, thinking it sapped the zeal from young ministers). So he accepted a circuit of churches, on which he would be the junior minister. However, when the senior minister learned of his desire to attend college, he released him to pursue that dream. Thus, Daniel Shuck ended up attending college for one year, focusing on courses which would help as a minister of the Gospel.

While in college, ministers from another denomination tried to lure him away with promises of a good church and financial security. He told them, “If you think a horse and buggy, fine clothes, and a good living are enough to buy me, you’ve misjudged me. I’m not on the market.”

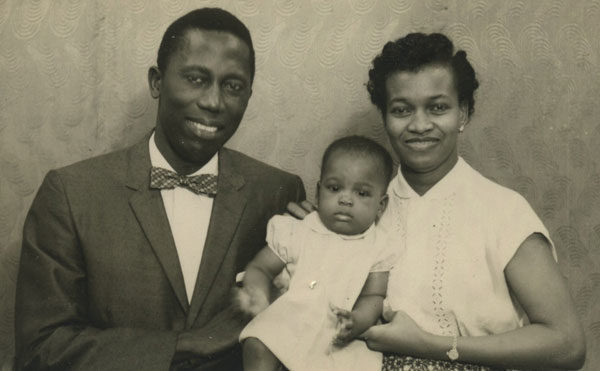

Daniel and Harret Shuck were married in 1847. They never had their own children, but they took in many other children in what was described as “a kind of orphan’s home.” Harriet often traveled with her husband, a true partner in ministry. He led devotions every morning in their home, and she led devotions at night. Early in their marriage, they resolved to not go into debt for living expenses, and to not keep a tab with local merchants.

After ten years of pastoring circuits in Indiana and Kentucky, the Shuck ventured West. In 1858 he became a missionary to Missouri. UBs, with their anti-slavery stance, were not welcomed–and, in fact, sometimes found themselves in danger–in Missouri, and were eventually forced to abandon their work in the southern part of the state. But Shuck was accustomed to such opposition, having pastored a circuit in southern Kentucky. Next came assignments on the west coast–in Washington, Oregon, and California.

The 1861 General Conference elected him as bishop of the Pacific District. He was a mere 34 years old. The Civil War had just started; a dozen of his fellow Indiana ministers had volunteered for the Union army, and he felt he should remain in the East, in case he was drafted. However, when he learned that the work in California was on the verge of falling apart after the tragic death of their leader, Israel Sloane, Shuck and his wife boarded a steamer in New York, crossed to the Pacific through Panama, and arrived in San Francisco 35 days later, in March 1864. From March through August, he criss-crossed central California, preaching and rallying the demoralized UBs. When they held their annual meeting in October, people who had predicted the end of UB work in California now felt hopeful about the future.

The Shucks also visited Oregon. On the way back to California, they encountered two robbers who shoved a cocked revolver into the bishop’s face and demanded all of his money. He was tied up while Harriet was searched. All of their money and some of their possessions were seized, but they were unharmed.

Shuck was re-elected bishop in 1865. During that second term, he organized Walla Walla Conference in Washington. In Oregon, Philomath College was founded in 1865, and when the Oregon churches held their campmeeting in 1868, over 2500 people attended the Sunday service.

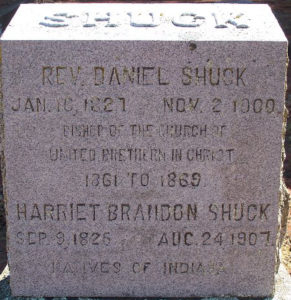

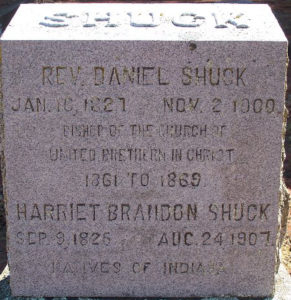

The tombstone for Daniel and Harriet Shuck. (Click to enlarge)

The 1869 General Conference seriously considered ending our involvement in Sierra Leone. But

Shuck gave a compelling speech on the conference floor, urging us to stay…and it turned the tide. We stayed.

When the 1885 General Conference established a commission to change the UB Constitution and Confession of Faith, Shuck saw it as a great blunder which could divide the denomination. But when Bishop Milton Wright led our group away, Shuck was not among them.

Daniel and Harriet spent their latter years, from at least 1889 on, in California, serving various charges in the San Joaquin Valley. In 1897, they celebrated their 50th anniversary. He passed away in 1900, and Harriet followed in 1907. They were buried in Woodbridge, Calif.